Gurry into Caviar (an Epilogue Written in 1996)

The increasing diversity in Kodak's seafood industry in the seventies was probably

due to several factors: improved fishing technology, successful marketing efforts,

and the Japanese. There’s a joke that says you should never take a Japanese guy fishing

or he will eat your bait. That has become progressively less funny over the years

as products once ignored by Americans suddenly become cash crops. The Japanese had

been harvesting North Pacific bottom fish and crab for years before Americans took

economic and culinary notice. Pioneering outfits like Wakefield Fisheries of Port

Wakefield and later Port Lions were among the first US firms to harvest, process

and market Alaskan King Crab, the product that revitalized Kodak’s canneries and

ushered in the era of year-

As a young boy I frequently helped tie up the Evangel in places like Alitak’s Lazy

Bay Cannery, where the water and pilings were thick with “gurry,” probably a mash-

In the summer of 1966, I crossed paths briefly with one of the Japanese work crews,

a group who had come to Ouzinkie to set up a caviar processing operation aboard the

processor barge Am-

Now, in the two decades after I moved away from Kodiak, (summer of 1996 as this is

being written) the Japanese have their own fish hatcheries, harvesting salmon without

buying it from Alaskan fishermen. The ADF&G authorized dumping of tons of pinks in

the ocean due to lack of demand, and half of last year’s harvest is still in cans

in the warehouses, unsold. No one fishes King Crab locally, and the shrimp harvest

diminishes yearly. People speak of dollar a pound salmon yields and fifteen-

What does it mean? The same flexibility and imagination that helped transformed gurry to caviar in my childhood can find new and exciting uses for the great riches of the North Pacific. Think of how the islands rebounded after losing so much in the 1964 Tidal Wave. It can surely happen again. The new fisheries research facility in Kodiak and even the salmon subs at Dick and Sue Rohrer’s Subway are signs of hope. Perhaps the wasteful and extravagant days of “get all you can get, with as many boats as you can,” are over, but I am sure that the rich Pacific Ocean will continue to yield lucrative surprises for this generation and succeeding ones if those who depend on it will work together with imagination and responsibility. — Timothy Smith, 1999 (revised 2020)

A fishing boat passes below the Near Island bridge in Kodiak channel, 1996, on its way to find another cash crop from the bountiful seas around Kodiak Island.

Cannery Work (Shore Life in Kodiak in the 1970’s)

By Timothy Smith, Originally posted in 1999, latest revision in 2020

Cannery Work

One of the first five articles on Tanignak.com, 1999

Introduction to the 2020 Revision and Re-

I wrote the original text for this article back in the mid-

I have NO current information on cannery work,

in Kodiak or anywhere else! (Sorry)

So this new 2020 edition of my article features a lot of newly-

The Original 1999 Article

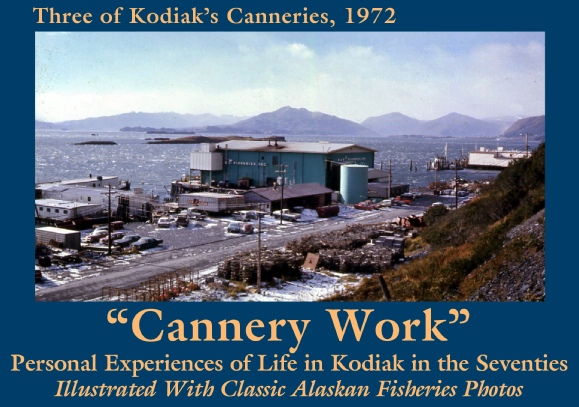

Cannery work: what an ancient and honorable profession, the very essence of life

in Kodiak. Cannery work: the stuff that dreams are made of, your ticket to Outside,

made bearable by its seasonality. You get pounding machinery, clammy green or yellow

slickers, unmaneuverable black gloves, wall to wall slime and goo, indescribable

odors, frigid water and scalding steam, a repetitious routine that would drive a

robot to suicide, eighteen-

If you want to reach the soul of these islands, and can’t get on a fishing boat,

throw your heart into cannery work. Come prepared to acquire an unshakable cat-

Left: Here is where we go fishing and then process the fish, go crabbing and then process the crab. No, not the moon! Kodiak, the island at the bottom of the screen! (NASA photo) Right: Somebody has to process all the creatures that the fishing boats bring in, and that’s where you come in if you choose CANNERY WORK! (Voyager photo courtesy of Bill Torsen)

From Everywhere!

In my own career as a cannery worker, I thoroughly enjoyed most of the people I worked

with. Their life situations were fascinating; Kodiak may have been a very remote

community in a far corner of Alaska, but the world had surely come to it. I saw illegal

aliens hiding from the INS, and even saw a raid, when the officials came and rounded

up half our crew (including, some of the boys lamented, the “cutest girl”). It was

fun to try to get to know people (as well as could be expected in the noisy and busy

environment of an operating cannery). One young coworker, a local boy like me, was

a member of the Kodiak Volunteer Fire Department. When the siren went off there would

be a blur and a pile of yellow rain gear as he sped off to serve. (Why are Kodiak

hydrants painted yellow? So you can’t tell where the dogs have been.) But sometimes

the majority of my co-

I tried out horribly mispronounced Russian on a recent émigré, learned Spanish cannery vocabulary from a Mexican named Jesús, discussed fine points of theology with the son of a Russian Orthodox priest and even made a normally stoic Japanese coworker laugh out loud by attempting to sing the words to “Sukiyaki.” One of the most unforgettable guys I met was a quiet, intelligent young Vietnamese man I met in the summer of 1975. He turned out to be one of ARVN’s best fighter pilots, who took his plane to Thailand two days before the fall of Saigon. He lived with a Viet Cong death threat if he ever tried to go back for his wife and child. He told me how he had thought of trying to get an American pilot certification but gave up when he saw that he had more flight time (most of it in combat!) than any of his instructors. He couldn't see himself flying again. His war had come to an end in an Alaskan cannery, far from the painful memories of the cockpit.

I found life much more bearable by trying to make friends, and almost everyone seemed

to have a story to tell. The days went by much faster when the crew congealed into

a joke-

Top: Cannery workers resting for a moment during salmon season, Larsen Bay, 1997. Bottom: Andy Anderson’s sequence of the Fortune’s haul of salmon, off Spruce Island, 1963.

Crab Butcher

My first cannery job was in the late summer of 1971, working the king crab season

at the Star of Kodiak, a rusting converted World War II Liberty Ship that the locals

had dubbed the “Scar of Kodiak” because it obliterated so much of the view of the

Near Island channel. Like many things done in Kodiak in the decade after the Tidal

Wave, hauling a war-

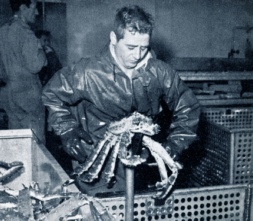

In the summer of 1971, deep in the bowels of the Star of Kodiak, I acquired something resembling a trade: I became a King Crab belly butcher. Now crab, like lobster, must be processed alive, or at least comatose. The procedure went something like this: you stand in your yellow rubber suit before what appears to be a guillotine blade pointed at your navel. Your own innards are protected by an apron made from old conveyor belt tied around your waist.

You select the nearest crab from a hopper that has been filled in the teeming hold of the boat below, grab him* by the rear legs (checking for the characteristic stiffening reaction that tells you he’s alive) and run him into the blade, pulling his leg sections off in one fluid motion. The leg sections go off to the gillers who grind off their gills in whirling metal rollers, and then on to the massive cooker by means of a conveyor belt of wire mesh. The shell and the tail of the hapless crab hang on the blade like a discarded bicycle helmet. These shells are thrown into a large grinder, which pumps the mess away.

* I’m not being sexist here. Any female crab was supposed to be thrown back while the boat was out at sea, to help preserve the species.

That sounds simple enough. But crab that have just been removed from the convention

they’ve been attending in the nice, cool holding tank and tossed unceremoniously

into a steel hopper soon live up to their name. A fifteen-

Now after the first hour or two of this constant impaling and dismemberment, your

boots are ankle deep in a shivering mass of what appears to be opaque jello, and

your arms are soaked to the elbow with liquid crab juices that soon solidify into

a cast-

My lead man at the Star of Kodiak was a crusty, hard-

On numerous occasions when my still youthful curiosity got the best of me and I strained

to see what was happening outside, he’d gruffly call out “Take Five!”, raise one

slimy glove open-

Above: Detail of Dirk Sundbaum’s early 1970’s slide of the Kodiak channel.

From left: The small boat harbor and Kodiak Airways’ seaplane terminal, a small cannery, the Liberty ship cannery called the Star of Kodiak (Alaska Packers Association, my first cannery job), and the ferry dock with the Baranof Museum on the shore behind it.

A Dismal Season

Now the foregoing is more or less how a King Crab is supposed to be butchered, and

how it was done, with minor variations, at processing plants all over the North Pacific

and Bristol Bay. I once participated in a program that was a notable exception. I

won’t tell you the name of the cannery, but its initials are “Bacteria and Bones.”

I was employed there, picking little fishies out of raw shrimp as they head toward

the peelers. (By the way, only a very few workers get to work at the same cannery

from season to season. Most of us took whoever was hiring, employed until the end

of that "run" and then were out on the docks looking for work again.) The foreman

came up to the shrimp line and put out the word that they had King Crab on the way

and was there anybody who was a crab butcher? Since picking little fishies out of

the cold raw shrimp as they head toward the peelers is an all-

What followed was, as they say, a millstone in modern seafood processing. The crab boat had already arrived, filled with rapidly expiring former residents of Bristol Bay, and my foreman hadn’t a clue about how to set up the program. He placed a butcher blade way out in the middle of the floor (at least he had a blade), brought me a hopper cart brimming with lethargic crab and told me to go to it. Just in case I had forgotten how to butcher, he grabbed a sample hapless victim and, swinging it over his head, brought it down on the blade, splaying the crab in unrecognizable chunks all over the floor. I told him politely that I was a “belly butcher” and would he be so kind as to bring me an appropriate belt.

Having established the method of execution, the next hurdle was the disposal of shells

and tails. I had quite a pile building before the plant engineers came around lugging

a contraption that resembled a large portable generator with an opening on top about

a foot square. This makeshift garbage disposal was then placed strategically near

a trough in the floor. The situation was a little like the carpenter who sawed a

board off three times and it was still too short, because those crab shells would

not go down that one-

A brilliant solution was proposed: we (I had been joined by the volunteer fireman guy) were to butcher the crab out on the face of the dock and throw the shells onto the rocks below the dock (I have always wondered which state official went blind...). So up came one of the planks and we got to butcher outside. Admittedly it was quieter and more interesting outside, so that we didn’t notice the cute purple pile of shells slowly growing on the rocks below. Apparently, the tide was supposed to casually come in and wipe our guilt away, but as always in Kodiak, nature steadfastly refused to cooperate. By the end of the third day, the shells were jammed all the way from rock to dock, and we had reached the point of another brilliant management decision. In addition, difficulty became crisis upon word that the health inspector was coming.

We were quickly dispatched under the dock with shovels and shrimp pitchforks to try

and dislodge the shells. There we discovered such a fragrance of loveliness that

it defies all attempts at polite description. Alaskan kids, born and raised around

fish parts and cannery goo, can stand almost anything. But this was surely our limit.

It seems that our little experimental pile of shells had been strategically placed

by mad luck in the path of the hot effluent from the shrimp cookers. The result was

the strongest, most putrid ammonia-

As the last few shells reached the water, I looked up through the planks and noticed my boss, standing there with the plant superintendent and the health inspector. By this time I'd just about had it with the whole operation, which made APA’s methods over at the Star of Kodiak look like the White House dining room by comparison. I looked up at them and burst out angrily, “You know, I really hate having to cover up for other people’s mistakes!” My coworker’s words on the subject were shorter, less printable and (wisely) less audible, but our facial expressions and their own nostrils confirmed our words. My boss meekly turned on his heels and walked away.

Surprisingly, I stayed with B & B cannery the longest. I worked as handyman and painter when processing slowed, and quit in late spring to go help at Camp Woody. In hindsight, it seems like there was an unspoken rule for success in the canneries: “Talk straight, but cooperate.” If the boss pegged you as a goof off or one who got too drunk to be safe, you were out. Cuss out the boss and you were definitely out. Taking unauthorized days off meant someone else was hired to take your place. But occasionally stating a differing opinion (while doing what you were told) never caused me any trouble. It seemed to be part of the Alaska culture at the time. I worked my tail off for all my cannery bosses through the years, so my occasional bluntness just gave me a reputation as someone who could be trusted. The rural Alaskans tend to be straight shooters about some things, and work was one of them. Everyone always had an opinion about how you tied up your boat, how you navigated, what brand of outboard motor you had. Some of the verbal interchanges that seem normal in a village would seem intrusive and rude to an Outsider. I apparently carried some of that over occasionally into my own work world.

The rest of that crab season turned out to be just as dismal as the first episode.

A new grinder was installed, and this one worked. We got a steady flow of crab and

I got a lot of hours in. However, all during that season most of our King Crab came

from Bristol Bay, a terrifyingly long way to try to keep the crab alive in their

overflowing holds. You have to admire those crabbers. In order to keep the crab alive,

you have to fill your tanks, which nearly sinks your boat. I have occasionally hitched

a ride on a fully loaded cannery tender, hoping and praying that the waves washing

over the decks like a submerging submarine aren’t going to take us on down. The treacherous

waters between Bristol Bay and Kodiak were immortalized in local lore as the “Cradle

of the Storms.” Hardly a season went by but some fully loaded crabber would succumb

to those waters, leaving yet another group of bereft families and grief-

As a result of their long journey, often most of the crab were dead by the time the tired crabbers tied up in Kodiak. My job as a butcher was to sort the fresh, live, sweet crab from the foul, soggy, dead crab. That’s because King Crab share the distinction, with similar species, of releasing digestive juices and intestinal bacteria into their bodies once circulation stops. If the boy is limp, he’s deadly. The only good crab is a moving one! The manager of the plant came by and repeatedly told us to let some of the ones who had seemingly only recently expired through. Did anyone remember in all the fuss that we are dealing with food here? I did my best to keep the foul ones out, but often the foreman would check the discard pile and throw some of them into the cooker. This happened repeatedly for most of the season. I did my best to salvage only good crab, and others did their best to make sure they didn’t waste any good money. It was a measure of the whole season that the entire shipment of crab was confiscated in Seattle and destroyed when the health authorities found an inexplicably high bacteria count in the crabmeat! (Continued below…)

Photos of King Crab processing courtesy of Wakefields (color) and Yule Chaffin (tinted)

Left: The object of our affection. Right: A whole hold full of them!

Left: unloading the hold. Center: getting the crab hoppers inside. Right: NOT a belly butcher!

Left: Freshly-

The color slides are courtesy of Lowell Wakefield, and the tinted book scans are from Alaska’s Kodiak Island, by Yule Chaffin (All used with permission).

Other Cannery Adventures:

The Mean, the Cold, and the Just Plain Dangerous!

There was an ever widening variety of seafood being processed in the early 1970s, and King Crab was not the only kind of crab I worked on. The Dungeness were easy to process: cook whole, wrap the legs in rubber bands, package and freeze. The real challenge with Dungeness was before the cooking. Inherently fast and bad tempered, they are the Africanized Honey Bees of the crab family. They can easily snap a pencil passed within their line of sight, and are almost too fast to avoid getting your fingers pinched, thick black glove and all. And like little aquatic Pit Bulls, you have to practically destroy them to get them to let go.

My own mental description of hell comes from the time I was asked to do a seemingly

simple task: throw live Dungeness crab out of a drained holding tank and onto a conveyor

belt. The crab were absolutely furious at losing their water, and out of breath or

no, succeeded in soon dangling from every appendage of my rubber rain suit. They

crawled malevolently off the conveyor belt faster than I could throw them on. I was

considerably slowed by their tenacious grip on my sleeves, pantlegs and anything

else within reach. On more than one occasion I was forced to throw one violently

across the tank, impaling it on the support bars of the conveyor belt in an attempt

to get my glove back! My own adrenaline-

Yet another variety of crab crawled its way into profitability in those days: the

Tanner or “Snow” Crab. Because the processing of Tanner Crab was a relatively recent

development, it did not have a long season. Many of the methods seemed experimental,

and not all were successful. There was even an attempt to change their name in honor

of King Crab and call them “Queen” Crab. The “Snow” label eventually stuck with most

processors. Tanners were very different from King Crab, being thinner, spindly, and

more spider-

Processing the cooked Tanner crab was another of those tedious, repetitive, “Who

the heck ever thought up this one!” kinds of jobs. We had to stand for hours at a

spinning blade and cut a line around the claws at just the right points, so that

when thawed, the meat could be extricated easier. I grumbled to myself that any flatlander

who can’t figure out how to get the meat out of a fully cooked crab leg after all

the trouble we went through to catch it, deliver it live, kill it, freeze it and

package it deserves to starve. It was always ironic to think that our rough, raunchy

and rugged Alaska coastline had produced so many hoity-

The coldest job I ever did for the canneries was work in the Halibut freezer. The

halibut is a fine fish, perhaps the best tasting of all the white meat fish in the

world. (Ask Shirley Le Doux for her fried halibut recipe, or Mom for her mushroom

and cream sauce baked halibut, and even the most hard-

Aside from being delicious, halibut’s other claim to fame is that they are BIG. Halibut

approaching 200 lb. were not uncommon in Kodiak waters then, and I swear I had to

move every one of them. When they were unloaded from the fishing boats, the halibut

were commonly sprayed with a saline solution, stacked on pallets and placed in an

enormous drive-

Of all the bounties from the sea, Kodak’s most famous, especially in the early days,

was Salmon. I never had much of an opportunity to work with salmon directly, but

of course I had seen every stage of the operation as a boy in numerous canneries

around the Kodiak Island area. I had a short but memorable career working salmon.

The few days I worked salmon was as a fill-

I was to pick up any stray fish heads, collect them in a bucket, and dump the bucket

into a chute that went to the grinder. It was a Sunday morning, and I thought I was

going to get the day off, but they called the workers in because of the arrival of

the load of salmon. I was tired (this goes without saying in a discussion of cannery

work) and I was wishing I could be over at the Community Baptist Church instead of

standing there all slimy and, well, fishy. I absent-

Classic photos and post cards of salmon canneries in operation

Right: a lovely time exposure (about 15 minutes) on a super calm night of the Sea Quail in the Kodiak channel with her crab pots glowing in the floodlights, ready to head out again.

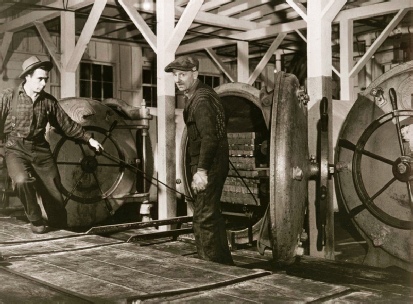

The salmon arrive at the cannery, by seiner (above) or by barge (an old-

Top: the salmon is cut up and placed, by hand, into cans. (A post card from Metlacatla) Then the cans go into the retorts to be cooked under high pressure steam, then let out to cool in big racks, and finally, the cans are labeled, and placed in cases to be sealed and shipped to market. (Last three photos are from British Columbia)

Shrimping and Other Sorrows

The longest season of them all belonged to shrimp. I spent a couple of winters keeping body and soul together working in various aspects of shrimp processing at B & B, APA and East Point canneries. One of the cleanest jobs in cannery work, there is little of the slime and grime associated with salmon or king crab, for example. The main drawback is the odor. Shrimp carries a pervasive smell that builds up on your clothes and greatly impairs sociability. I often had to rush directly from work to my night classes at the community college during the winter of 1972, and believe me, I sat alone! In Kodiak, people do understand such things. It is the smell of money.

Working with shrimp was by no means all sweetness and light. One of the most tedious and uncomfortable jobs in the cannery was the task of sorting the fish, rocks and seaweed out of the raw shrimp before it went to the cookers and peelers. The shrimp was unloaded from the boats by cannery workers with big pitchforks, who filled giant hoppers that were winched up to the shrimp line and dumped unceremoniously into a big vat of water with a wire conveyor belt at one end. This belt dumped out onto a wide belt that led to a vat of fresh water, and then on to the cookers and peelers.

Along this wide belt were positioned workers who stood and picked out unwanted items such as little fish and seaweed. As with other cannery jobs it was deceptively simple. First, the raw shrimp came up from the boats packed in flaked ice, and the first vat of water never removed all of it. Next, the work stations were practically outside, beside a large open hatchway for the hoppers, and it was winter. Finally, the thick, insulated black gloves with cotton inner gloves were still incapable of keeping out the cold or preventing the sharp nose spikes of the shrimp from puncturing our fingers. Cases of blood poisoning and finger infections were relatively common.

It really should be added that gazing for hours on end at the moving conveyor belt

had a strange, hypnotic effect. You could always tell when someone had been doing

cannery work too long by the way they picked imaginary fish off the tables at coffee

break. Left, right, pick, flick...your mind could definitely take a walk. As a freshman

and sophomore in college I used this fact to my own advantage. When working ten-

Sometimes, when boredom would completely overcome us, above the din of the machinery

someone would start singing. And like the little Whos down in Whoville, anyone else

who spoke that particular language would join in. We made passing fair imitations

of the Four Seasons, plus choral versions of Elvis and the Beatles. Through our earplugs

we sounded great, but our foreman thought we sounded like inebriated pirates and

made us shut up whenever his boss came around. On days like that you could almost

forget the freezing, aching fingers, the low-

The shrimp came to us in large trawlers designed specifically to scoop up as many of them as space permitted. The typical modern shrimp trawler was a large metal craft with a high, squarish stern and long, cage like booms on either side. The Star of Kodiak, for example, had a whole fleet of them, called “Bender” boats, after their manufacturer. With names like Rio de Plata and Mar del Este, and registered out of New Orleans, most of them were painted the ridiculous seasick orange color of the Alaska Packers Association. They also had the rumored reputation of being able to find the bottom of the ocean in under three minutes.

I Only Have Ice for You

Shrimp boats never left the dock empty during shrimp season. They loaded with tons of chip ice to pack the shrimp in. One of my tasks while working shrimp at B & B was to go up into the refrigeration tower and shovel chip ice into the trawlers. There was a large metal corkscrew in a trough that ran the whole length of the ice room, and it was supposed to pump the ice into a chute and down into the hold of the trawler below. But the ice always piled up on either side of the screw so it required a couple of guys with shovels to keep it operating. Our cannery boots had no treads to speak of, and so we gingerly began the task of navigating the mounds of ice with enough leverage to shovel the chips.

Now the safety switch was at the chute end, while we were shoveling away high on

the mounds of chip ice at the rear. My coworker slipped and fell on the edge of the

trench, and his snow shovel slid down into the trench with the corkscrew. Like a

mime pretending to walk downstairs, the shovel got progressively shorter as the corkscrew

went chunka-

Above: the Pioneer, a legendary old “halibut schooner,” and a shrimp “Bender Boat” tied up at the Star of Kodiak in the channel in Kodiak, summer of 1971.

Below: a Gulf-

Left: The “Lazy Bay” cannery in the late 1950’s, with gray “gurry” visible near the dock and even in patches across the bay. Right: two modern fishing boats enter the channel in Kodiak in 2010. New fishing boats are set up to harvest a lot of products that would have become gurry years before.

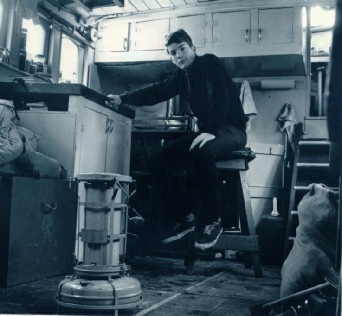

Left: The author, Timothy Smith, as a young cannery worker living on the Evangel

in the small boat harbor in Kodiak in the fall of 1972. A bag of very cannery-

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-

To do more exploring at this site, click on the links below,

or click the Tanignak.com logo