Preface to the 2020 re-

When I wrote the handwritten original article in my spiral notebook back in the 1980’s,

I was still working at the phone company, and had yet to become a teacher. I began

my teaching career at age thirty-

Original 1999 Author's Note

Unlike most of my articles, this one is written in the past tense, allowing me to more easily share events of particular years of my education in Ouzinkie. Although the experiences of other of my classmates might be similar, this individual approach is the only way I can adequately explain what school time was like in Ouzinkie during those years. By the way, I am impressed with what I hear regarding student performance and morale in the “new” school, which unlike mine, includes grades through high school. Staying in the village instead of having to board away from home is a wonderful benefit! But with this article I hope to have given a fair account of student life in Ouzinkie ‘back in the day’ when I attended (eighth grade class of 1967).

–Timothy Smith, March, 2020

An Old Village School (That Sometimes Got Upgraded)

The Ouzinkie School was a necessary center of activity during the winter months,

but one that meant lessons and homework and sometimes eccentric teachers. The village

of Ouzinkie had long been too large for a fabled “one room schoolhouse” of pioneer

days, but there was an undeniable charm to the old grade school nonetheless. It was

a large, multi-

The villagers finally got fed up with the poor location, had mercy on their children, and built a large elevated play area, supplied with basketball hoops. “The platform,” as it was known, was the main place to play most of the rainy season (what am I saying? most of the year!), unless you favored wet shoes. Even in the snow it was a great place to dive from or use as a snow fort. Near the platform were the outhouses or “nooshniks,” which being of poorer foundation and smaller mass than the schoolhouse, always tilted at odd angles. I think that feature may be a prerequisite for outhouses! No matter how many boards were laid on the path, the trip to the outhouses was always a soggy proposition. Nobody was unhappy when they were replaced in the early 60’s with indoor plumbing.

In my early years there, the school’s classrooms were poorly lit by low wattage bulbs powered by the low voltage cannery light plant. Then in the early 1960’s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), or perhaps the fledgling Alaska State Government, in a fit of unaccustomed generosity, decided that improvements were called for. The school got dependable power, adequate lighting, and a real sewer system. From then on it was flush toilets and fluorescents. The school power came from two dark blue diesels in their own shed, which added a substantial hum to the school day. It is local lore that when the pilings for the power shed were being driven, the work crew on a lark decided to see if they could find any bedrock under the school yard. They gave up after eighteen feet of solid sog. So the old school always sagged and creaked at odd angles and shook with the pounding of busy feet.

Recess Scenes At School in the Mid-

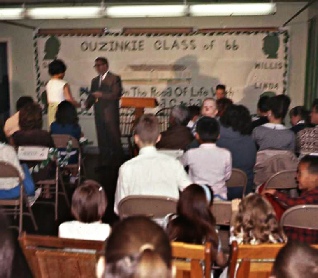

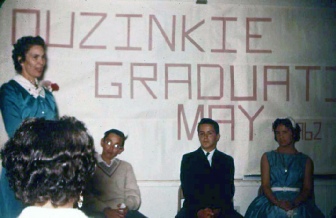

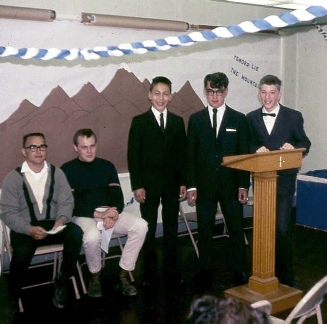

Eighth Grade graduation, May 1967. L to R: School Board member Nick Pestrikoff, a guest whose name I can’t recall from Kodiak, and the three proud graduates, George Katelnikoff, Chris Boskovsky and Tim Smith. The podium and electric piano, (and Mom to play the graduation march) along with most of the chairs, were borrowed from the Mission.

Original Conclusion to the 2006 Revised Posting

I am in my early fifties now, and have been a high school reading teacher for many years. When I was a sometimes struggling elementary student in Ouzinkie School, the thought that one day I would be a teacher would have seemed foreign and even appalling. As I reflect on the long pathway of my own progress as an educator, I can't help thinking of my eight years at Ouzinkie School, and the teachers who came in and out of our village during those years. I can see traces of them all in my own classroom, either in what I do or in what I try to avoid doing. I know I wouldn’t think of passing around pictures of people wearing an Alaska Flag, for example, and we’re not allowed to use spruce paddles with holes in them! But how I teach struggling readers, or how I approach a good piece of literature – these things come from teachers I had back in the village. I should hope those Ouzinkie School teachers could count me among their successes. (Written in 2006)

Conclusion to the 2020 Edition

How time flies! I am now a retired teacher as of May, 2018, with a 29-

The main character is the son of a small village’s only schoolteacher, who moves

from Arizona to a fictional island in Marmot Bay, close to Afognak Island. The novel

includes a lot about being in a village school with not only multiple grades, but

also multiple ability levels. To make the story realistic, I really had to put my

mind back into the grade school classroom, and for that, I had to remember what worked

and didn’t work about the two multi-

The school and the teacher are not the main focus of my novel, but the school served

as a prime location for many of the important plot developments. Since the plot covers

a school year (1963-

Thanks for checking it out! –Timothy Smith, March, 2020

Ouzinkie School Memories: the 1960’s

By Timothy Smith, posted in 1999, latest revision in March, 2020

Ouzinkie School Memories: 1960’s

An Article and Photo Album About the Village Grade School in

Ouzinkie, Alaska in the 1960’s

The Ouzinkie Grade School, with its platform and playground equipment, as it looked in 1966. The swing sets were purchased with funds raised by showing old 16mm movies every Friday night during the school year. The top photo was also in Yule Chaffin's book, Koniag to King Crab.

Ouzinkie Grade School as it appeared from halfway up a tall spruce tree in 1966.

Clockwise from Top Left: A soccer game, George and Gary relaxing by the “platform,”

Mr. Frobin Putman, my teacher for two years, and me sitting on a kids’ rocker, “nooshniks”

and the platform behind me, wearing rubber boots on slippery ice. (1965-

What Sort of Education?

What sort of education could be had in a BIA village school? Although it could vary

as widely as the qualities and capabilities of the teachers, it was considerably

better than smug Kodiak educators gave us credit for. In the early days, a village

kid who transferred to the Kodiak city school system would be routinely dropped a

grade, but soon a number of outstanding village-

When was the last time you tried to use real horse hoof glue? We had some, and it is everything it is purported to be (other than an effective glue). For the first few years, I didn’t just receive my grandparents’ education; I probably even had some of the same textbook titles! Social Studies books were all reverently patriotic and often critical of Indigenous peoples, health books were blissfully ignorant of socially significant developments, and Dick, Jane, Spot, Puff and a teddy bear unfortunately named Tim reigned at reading time. Without the wisdom of the Whole Language Method, Cooperative Learning, Madeline Hunter, or whatever the latest trend in South 48 education was, we sloshed through endless phonics workbooks, spelling tests and handwriting drills, and consequently learned to read and write. As a teacher of students who can’t spell, or sound out unfamiliar words, to whom cursive may as well be cuneiform, I appreciate the “old school” methods I was subjected to.

Audio-

When the modern world did intervene in our behalf, it was often to our detriment.

There was the time we were all administered a standardized test from somewhere civilized,

which involved identification of “common” shapes and objects. How many village students

had ever seen a suburban gas station, or a fire hydrant? What would we know of plows

and tractors or taxicabs and newsstands? On the other hand, which of the educators

who thought up that instrument could hold forth on leaded seine lines, power blocks,

the difference between a “humpy” and a “red” salmon, or the distinctions between

a Johnson and an Evinrude? Not surprisingly, too much of this treatment often prompted

native children to rebel against “American” education as being anti-

My Fellow Students and their Younger Brothers and Sisters

About those Teachers

In spite of the occasionally unhelpful curriculum, the biggest variable in my grade school education, as it would be for any student, was the caliber of the teachers I had. The people who chose jobs as village teachers in those days were largely a hardy lot, intrigued by the adventure and novelty of working in an exotic, isolated environment. But there were sometimes darker motivations. Teachers whose record elsewhere was cloudy, who had experienced “problems” in another location, often found the BIA application process blissfully vague. The village school system sometimes got teachers who might have been unemployable elsewhere; it was said that the original builder of the village cannery had raised his money from funds siphoned off the village school budget, but of course this was never proven. And on at least one occasion, Ouzinkie got a couple who were so green at teaching and so unsuited to village life that they made a mockery of the profession and nearly disbanded the school. On the other hand, those who answered the challenge with a pure motive, a heart for the kids, and a willingness to do the hard work were among the best examples of the teaching profession that could be found anywhere.

My first grade teacher, Mrs. Lassiter, left only faint impressions on my memory. I recall the reading drills and Herman throwing up in the wastebasket, and my sister’s friendship with her daughter, but that's about all. Ah, but second grade was much more memorable, and a near disaster for all concerned. At that time, Ouzinkie Grade School had enough students to warrant three teachers and three classrooms. There were Mr. and Mrs. P. in their first teaching assignment (and unnamed here for forthcoming obvious reasons) and venerable, devout and large Mrs. Connor from Oklahoma, who lived in the tiny attic apartment over the big kids’ classroom. A few of the older students used to stand at the foot of the stairs just to watch Miss Connor descend. But that was the extent of the infractions allowed, for old fashioned discipline was the rule with her.

Some Official School Functions

Top: My Mom, Joyce Smith, speaks at the 1962 eighth grade graduation.

Center: A school Christmas program, 1965.

Bottom: Frobin Putman gives Wanda her certificate at eighth grade graduation in 1966.

These photos were taken by my parents using some of the inexpensive cameras people had back then, explaining how blurry or dark they are. But only a few photos of my school years exist.

A Regrettable School Year With Tragic Consequences

So my second grade teacher was one Mrs. P., a young and trendy blonde in tight, short

dresses who hated village life and said so, and who did not get along with Mrs. Connor

at all -

Not that the irrepressible Mrs. P. made the situation any easier, or modified her behavior to fit community standards (or even basic education ones). She soon circulated a photo of herself, apparently in the nude, laying back on a bed, and wrapped in nothing but the Alaskan flag (in honor of our new Statehood, of course!) The photo made the rounds among the upperclassmen (6th, 7th and 8th graders, for heaven's sake!) But I as a second grader somehow got a glimpse of it, and it was far beyond what I ever needed to see at that age! Mrs. Connor and half the village were appalled. The rest wanted copies. The end result of all of this was tragic from a small village’s perspective. Unfortunately, several of the families with multiple children made their temporary move to Kodiak permanent, changing the dynamic of the village for years to come. It was the year that learning lost out.

Top: my friend George crossing a stream on a hike to Mahoona Lake, October 1966.

Above Left: Davy and Cliffie at their home. Above Right: Joan, John, and Dee Dee.

Right: Rhonda, Thelma, Jennifer, and (in front) Patty in the woods near Otherside

Lake (1965-

Not Always Forgotten: A group of Rotary Club members from Kodiak help to repair the platform in 1968, as village kids look on.

Things like the photo, along with the village pitching in to get basic playground equipment for the school, were hopeful signs in a vacuum created by a distant government that kept hands off in the face of constant need. Such was the lot of village schools until the State of Alaska grew into its responsibilities and took rural students seriously. But the improvements came too late for me, as I was already graduated and gone when things started to change.

Unforgettable Personalities

The above account of my ill-

There was still plenty of room for the unforgettable personality or two, however.

My fifth grade teacher, for example, was a tall, poker-

The next two years I studied under Mr. Putman, who had once been a student of Mrs.

Connor back in Oklahoma. He told great stories, and was an easygoing fellow until

crossed, and then was a ruthless disciplinarian of the old school. Nose to the board,

feet on tiptoes for fifteen minutes was one of his favorites, but his paddle was

surely our least favorite. He had hand carved a stout spruce board about four inches

wide and perforated at strategic spots with half-

Preparing to Graduate

My last year at Ouzinkie Grade School was under the tutelage of Mrs. Luther, who was a fan of poetry and an excellent writing teacher. I had the great fortune of having her again as a creative writing teacher a couple of years later when I was attending Kodiak High School. I am sure that many of the creative ways I have developed for explaining a piece of literature or devising a writing assignment descend from her methods.

I graduated from the eighth grade in the Alaska Centennial year of 1967 with Chris

Boskovsky and George Katelnikoff. The theme for our graduation (all three of us!)

Was, “We have reached the foothills; yonder lie the mountains!” This was Mrs. Luther’s

exasperated suggestion when the only ideas the three of us boys had come up with

were irreverent or downright anti-

On to Kodiak for High School

As with all villagers who desired further education, I would have to move away from

home to get it. So I spent my freshman year taking classes from the University of

Nebraska Extension Division, a by-

Then in the spring semester of 1970, the high school dormitory was finally opened,

and for a year and a half, I experienced what a college student who takes up dormitory

life would have. For all my high school years, I saw my family only once or twice

a month. The experience of life in the Kodiak-

The author stands in front of his old school in March of 2002. The building says,

“Ouzinkie City Hall.” The playing field has the fire station now, and the area where

the platform once stood now has the old community center. And a few blocks away up

the hill is the school, which serves K-

For Tim’s novel, or more on the village of Ouzinkie, including many more historic photos, please follow the links in the graphics below.

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-