Camp Woody 70’s Memories

Camp Woody 70’s Memories, Stories, and Secrets

By Timothy Smith – written for the 50th Anniversary of Camp Woody, Revised and Expanded in 2020

This is a collection of various mostly unrelated subjects. I’ve made no particular

effort to string the topics together, other than that they are memories of Camp Woody

while I was a volunteer in the 1970’s. For a more orderly account, please see these

two articles: “Camp Woody 70’s Year By Year 70-

NOTE: This article is mostly light-

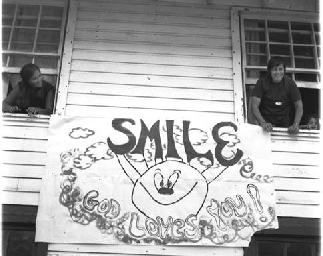

In the summer of 1971, a counselor named Nancy on the left and Marianne and Gabie Boko on the right hang out a poster that illustrates the spirit of Camp Woody throughout much of the 1970’s.

The Buoy Swing

This is the real, true story of a camp landmark, 1970 to 2005

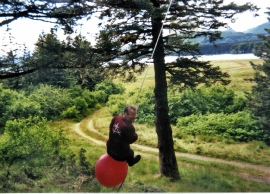

Lori Weisser enjoys the swing in the summer of 1971 (Travis North photo)

It is the summer of 1970. The Baptist missionaries of Alaska are holding a convention

at Camp Woody. Karl Childs, whose dad is pastor of Community Baptist Church in Kodiak,

and I (whose parents run the camp every summer) are bored out of our ever living

minds! Suddenly I remember a swing that my old friend George Katelnikoff in Ouzinkie

made in his back yard. The long polypropylene rope, tied to a high branch of a tall

spruce tree, had a wicked arc to it. So we go searching for a suitable place for

a similar swing. There’s a pair of tall trees near where the old board-

There’s only one person to ask for stuff like that: Darrell Chaffin. Darrell is the retired former station manager of the Woody Island FAA station, with a new log cabin up on the bluff. Lately Darrell has been making spare change storing crab pots on the meadow near the dock, using his old Dodge Power Wagon equipped with a boom and winch. If anybody has some spare crab line and a buoy, he does. Thankfully, Darrell has a soft spot in his heart for crazy teenagers, having raised two of his own. Soon Karl and I are busy measuring line and making a secure loop in the middle, tying the looped ends together with a generous length of sturdy halibut cord. Karl wisely allows for a lot of extra line on each side, because we’ll have to adjust it, and there has to be enough line to carry up the trees on both sides (think about it…it’ll make sense). Then we guesstimate the length of the drop from the loop to the ground, allowing for enough rope to tie up the buoy and reach the ground.

Karl climbs the tree closest to camp, and ties that half where he thinks it should be. I go and get camp’s tallest ladder, because the other tree has no branches for fifteen feet. Karl goes up the ladder, shimmies up the branches of the second tree (holding the rope the whole time) and tells me to help him measure the right distance. We come up with a reasonable approximation of center between the trees. Karl ties that side securely, and scampers back down. I get the buoy positioned where we can run off the hillside and leap onto it for our grand swing. We both try it, and are pleased with the springy effect the giant T attached to the two trees makes. When we jump on the buoy, we can see the two trees pull together and then bounce back, giving us a little upward thrust on the far end of the arc. Unfortunately, that is still pretty boring, for the arc of the swing is only about 20 feet.

I get an idea: how about using a ladder to get more height? We find a short wooden

ladder behind the Boy’s Dorm and prop it precariously about halfway up the hill,

tying some of the leftover crab line to the ladder and to a couple of little saplings. Karl

tries the ladder, which is a little shaky (suspended in thin air and supported only

on one side by ropes) and gets about twice the spring and twice the distance as previously. I

try it, too, and am still tragically underwhelmed. We give the swing a C-

The next day, I go to the swing alone, just to see if my C-

Left to Right: The first swing photo, of Karl Childs taken from the road below (summer of 1970). Note the treetops! Middle: I get ready to leap into space while my brother Kelly waits his turn (Mab Boko photo). Right: a photo taken from the road at the bottom of the hill, of the swing overhead. WHOOSH! (Travis North photo, 1972).

Left to Right: A 45-

Left: Still swingin! The last official buoy swing in 2005, from the bottom of the hill looking up, showing the full length of the ropes (wide angle, in the sunset). By that time, Ty Harper had replaced the rope, and built the nice wooden platform. In a world full of insurance payments and OSHA demands, this swing could never pass muster. But as a way to capture the joys of childhood, it was an unparalleled success, and lasted a good long time! WHOOSH!

Below: The author on the swing in 1998

The rest, as they say is history. For three and a half decades, the swing has been the stuff of legend: a place to explode your senses and prove your mettle, a natural high in every way. Granted, it wasn’t particularly safe, and a modicum of common sense was required, but it was one of the most beloved and memorable parts of the Camp Woody experience. Finally, in 2006, conscientious board members secured its removal (for which I bear no ill will, being an adult now myself!) But back it came a short time later for staff, not campers – the rope tied up into the tree and the buoy stashed away until no one is looking!

I can tell you when I worked again at Camp Woody as a young feller in his fifties that the thrill of jumping out into space and onto the buoy was as potent as ever! In 1998, when I had the privilege of serving as lay pastor for the Junior High camp, I walked up to the swing hill as campers took turns catapulting themselves into space. I overheard a few of the kids saying, “I wonder if the old guy is going to try it?” I calmly climbed the ladder, jumped out and onto the buoy, and enjoyed my turn. They were rather surprised until I told them, “Of course I love this swing. I designed it!” (Continued below…)

Oscar, the Camp Dog

Just a Dog, But A Great Citizen of Camp Woody

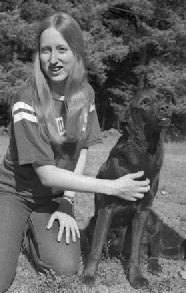

This section is not to put a dog on par with any of the wonderful people in this article. But Oscar was our brother. Kelly and I both agree on this, with no denigration of either one of us. Oscar was a mutt, probably Black Lab and Shepherd mix, but he was our brother. I have never known another dog that was as capable of immersing himself into the affairs of humans, or that could make as many friends as Oscar. Our sister Robin brought him home shortly after the 1964 Tidal Wave, much to the consternation of our parents, at least at first. After his “chew the shoe” phase, Oscar turned into a bright and cheerful companion, very well trained by his absolute lord and master, our Dad, Norman Smith. Oscar knew a lot of tricks, and loved to perform them. His weakness was not steak, but graham crackers. And he was an intuitive and empathetic member of the Smith household in Ouzinkie. But every summer at Camp Woody (from 1964 to 1977) Oscar really came into his element. He seemed to be everyone’s best friend, and never met a kid he didn’t like. Oscar often served as a bridge between the shy and withdrawn kids and the rest of us, because no one could resist Oscar. He was just a good guy.

Oscar loved the hustle and bustle of a camp full of kids. He would run himself ragged whenever the kids hiked anywhere, and plop himself in the nearest puddle to cool off. But he was polite at cookouts, only occasionally scarfing down a dropped hot dog. Anywhere near a Smith, he would know to wait until given the “ok!” before eating anything. And he was known to even bow his head at mealtime prayer, while carefully giving Dad a sideways glance to see when he was through. One winning characteristic of Oscar, at least in my mind, was that he didn’t lick. If overcome with emotion, he would push the top of his head against your leg and wag his tail slowly. He also was known to take your hand in his mouth while walking along beside you, which I guess is even worse than licking, but endearing nonetheless. Perhaps his strangest behavior was after the campers left. If Oscar thought he was alone, he would go up on the ramp that connects to cabin 4 and 5, look out past the volleyball court toward the dock, and moan. He never howled like most dogs. But after all the campers had gone, you sometimes could hear an almost inaudible, moaning “Ooo…….ooo…….ooh” escape his lips as he gazed upon the vacant volleyball court and empty roads. That’s strange behavior for a dog, but not so strange for our emotional little brother.

Oscar was not without his doggish flaws. His worst offence was that he would find some dead seal on the beach and roll in it, returning triumphantly to camp grinning from ear to ear, as if he had just discovered the world’s best cologne. We’d have to take a bucket of suds to him then. He also thought of himself as the guard of the camp, and barked appropriately at anyone who walked up the road from the dock (tail wagging energetically in a weird circular motion). Sometimes he would mistake Dad for a stranger until sight and scent corrected him. Then, as Marianne Boko observed, he would blush furiously (through black fur?), tail between legs and all teeth showing, while trying to bury himself beneath the clover. Dad would just pat him on the back and call his name, and all would be well. Another drawback was that he was a singularly inattentive regular attender at chapel services. Many a visiting pastor looked down below the podium with chagrin to observe Oscar snoring loudly, chasing something in his sleep. Everything was always forgiven, of course. The thought of banning him from chapel was never even considered; he was our brother, after all.

Oscar was never happier than when lying in the sun, surrounded by campers, front paws nobly crossed like some canine prince. Incidentally, when Debbie and I got married under the trees by Tanignak Lake in 1977, Oscar got his own boutonniere and wore it proudly as he escorted people to the ceremony. Ok, so I’m anthropomorphizing him an awful lot! But everyone who attended camp while he was there agrees he was a mighty fine dog. Four paragraphs about a dog, but he deserved it. (Continued below…)

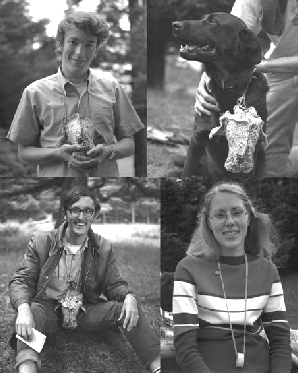

Carol Chapman discovers Oscar’s weak spot in this 1974 photo.

Swim Lake Switches

Camp Woody Adapts to a Changing Island

In the years after the Tidal Wave, Camp Woody had a problem. The beautiful Mirror Lake, which once had been a fine swimming hole, was now a brackish lagoon. Tanignak Lake, also close to camp, was the water supply. What to do about swimming? Finally an enterprising cabin group blazed a trail across the island to the far side of Ehuzhik Lake. They used old bed posts and planking to bridge the swampy areas, and created one of the most picturesque trails on the island. It wound its way through some of the original virgin forest on the north side of Ehuzhik, terminating at a sandy lake shore close to the ocean beach. The lake bottom was squishy and muddy, but a few yards out became a nice deep swimming hole.

This location was camp’s swim spot for almost a decade. But it was off Mission property. So some campers and I helped to blaze a trail to the other end of Ehuzhik, whose southwest corner is on camp land. This trail winds up and down some pretty steep hillsides directly behind High Inspiration Point on the hill above Tanignak Lake, before crossing some swampland into deep forest on the far side of Ehuzhik. It’s not as nice a beach as the other end, being made up mostly of flat gravel rather than soft muck. There’s also not a large beach area for sunbathing or campfires. However, kids have a deep swimming area just a few yards offshore. The other end of the lake, unfortunately, was the site of a plane crash, which scattered debris in the water and onshore, making it unsuitable.

In 1998, when I returned to Camp Woody as a lay pastor, I discovered a much-

Lovely Ehuzhik Lake (called “Long Lake” on government maps) in 1996. Since the Tidal Wave, three spots have been tried as swimming holes. The current one is in the middle of the far side, midway down the line of trees.

The far end swimming hole was very satisfactory, with a fine beach, until a float plane crash littered the shore and the floor of the lake with debris. The color slide is from Travis North, 1972. The photo below was taken in my tree climbing phase!

Don Wells took this photo in 1976 of a rainy swim trip on the near end of the lake. Not much of a beach, and deep water is a good ways offshore. The kid in the hooded jacket is Mat Freeman, now a respected local teacher, actor, artist, and camp board member.

Many years later, the camp settled on a deep swimming hole on the far side of the lake.

Ingenious Fixes and Untold Tales

Electricity and Water Supply:

Camp Woody’s facilities are mostly World War II buildings, and in the 70’s, the electrical

and water systems were of that vintage. This meant a lot of creative energy had to

be expended to keep the place up and running. Norm Smith, Bob Boko and various volunteers

from town often had to quickly improvise a repair that would hopefully last the season. In

the 50’s and 60’s, electric power was supplied by the Evangel’s spare generator,

for a couple of hours a night. The camp bought a funky propane-

The water supply was a different story altogether, and remains a challenge even to

this day. In the first decade or so of camping on Woody, the camp used an electric

pump and the Navy’s old intake lines to push water from Tanignak Lake past the camp

buildings up the hill beyond the swing and above the barn. There it trickled feebly

into a large, covered water tank (which we called the tower). The intake lines were

rusting, and the pipes from the pump to the tower were actually wire-

Then one spring, shortly before camp was to start (the usual time for disasters) we discovered that the wooden pipes had collapsed sometime in the winter. No matter how hard we tried, no water reached the tower, and we discovered a sizeable swampy spot where the water was leaking out. Dad, the Mission and various people from the Community Baptist Church put their heads together and came up with an elegant solution: a new intake line of PVC pipe, and a pressurized holding tank of about 60 gallons or so, right at the pump house, which kept the camp with a steady supply of water. The lines were tapped off just past the Boys’ Dorm, and the tower was retired forever. Its planks later got recycled as a new dam for Tanignak Lake, but that’s a story from the years I wasn’t there.

The good news about this new system was the added ability to chlorinate the water,

but the PVC water line (more like a three-

Above: Tanignak Lake, source of Camp Woody’s water supply, is a pretty and peaceful spot, even on a rainy day. (Tanignak is also the source of the name for this website, of course!)

Left: This portion of exposed wooden water pipe was formerly beneath the road bed

beside Cook Bay on Long Island. Camp Woody used this type of water pipe until the

mid-

The Untold Story of “Beef On Tap”

While we’re talking about water supplies and ingenuity and stuff, it falls on me

to share with you the infamous, semi-

Dad enlisted Darrell Chaffin’s help, who drove down with his red Dodge Power Wagon boom truck, some spare rope, and a large green canvas tarp he didn’t expect to see again. Thankfully, Darrell kept a little dinghy with an outboard pulled up on the near shore of Tanignak Lake, normally used for trout fishing, and that became a key component in our enterprise. Somebody took the boat down to the fallen tree and delicately roped the animal to the dinghy (I don’t want to think about that job!). It was a long haul to drag the carcass down the lake to where Darrell and his truck were waiting. He winched the bloated body onto the tarp spread on the shoreline. Then the whole mess was gingerly roped together and tied to his boom line. I say “the whole mess,” but owing to the condition of the cow, there’s no guarantee we got it all, and I suspect we didn’t. We’ll just have to let the matter drop.

By now the cow was wrapped in green tarp and suspended midair under the boom of the

Dodge. The next step was to slowly drive it through camp, around past the BOQ and

down the road to the dock. The drive through camp was the most delicate, because

we didn’t really want anyone else to see. We had sweetly asked some of the women

to please cook us up something nice (we thought it an acceptable trade to appear

chauvinistic when our real motive was the chivalrous protection of their constitutions

and the reputation of our water supply!) With nothing more to do, I ducked back

into the dining hall before the boom truck passed, and went to the far side, engaging

the ladies in some chit-

Emil Norton, Jr. was waiting at the dock with his little seiner. He had the inglorious

job of unhitching the mass from the winch cable and tying a length of rope to it

so it could be towed out into the channel. This accomplished, Emil eventually sent

it on its merry way (may it rest in peace, or at least in pieces). I don’t recall

if Emil stayed for dinner, but the rest of us guys took an unusual interest in washing

up beforehand, and I don’t think we had much of an appetite for awhile. Sitting around

the benches, sharing knowing looks with each other, we soon were swapping morbid

puns, completely over the heads of the ladies who had been kept out of the loop. Sometime

during the meal, after pouring a drink of water and saying “soup, anyone?” or “care

for some bull-

And to this day, Bruce, Cody, Kelly, Emil, Larry, Darrell, Dad and I have been the only ones to know this delightful tale, until now. And I hope my fellow conspirators will forgive me (and correct any errors). In the meantime, drink up! Nice, chlorinated Tanignak Lake water is among the best tasting in the world, and we had a small hand in keeping it that way in the summer of 1975. (Continued below…)

Left: A beautiful tree-

A Telephone for Camp?

To understand the novelty of a phone line, you have to remember that even though

camp was in sight of Kodiak, it operated as a remote and primitive site, as described

in the struggles to get water and power to work. In twenty years of operation, no

one had even considered trying to get a phone line in. The FAA had a full-

Darrell Chaffin, always resourceful, decided to try to locate the phone lines on the Kodiak side of Woody Island, to see if any of the pairs were usable after all these years. He found the cable, and its other end on the Kodiak side, and persuaded someone at the phone company to help him test each pair, with the hope of finding phone service. I don’t remember how many pairs the cable originally featured, but he eventually found five or six that still somehow worked! He then put in his own phone line, all the way up to his cabin by Una Lake, and brought another line close to the Camp Woody sign. Somebody installed a drop for the camp, and we got a phone.

I wasn’t aware of this ingenious development until one day I heard a phone ring in

the dining hall! This was not the usual CB radio traffic! Woody had always felt remote,

separate from town, an oasis of undomesticated serenity. I was of mixed feelings

on having a phone. But on the other hand, how cool is it to go and find an almost

four decade-

Today, of course, it’s a different story. And I’m sure it’s hard for many people

to believe how remote and “off the grid” things were at the beginning. Chaffin’s

cabin and the camp soon had microwave radio-

The FAA Goes Away

The Closing and Disappearance of the Woody Island FAA Station

Above Left: The FAA Station on Woody Island as it appeared when Darrell and Yule

Chaffin lived there, with green lawns and boardwalks. Two orange and white towers

can be seen in the valley to the upper left. Photo courtesy Yule Chaffin Collection. This

is from a color photocopy, so the color is a little off, but it gives a hint of how

neat and clean and homey the station was during the Chaffin years. Later, the houses

were all painted different colors, and the apartments in the rear left of the photo

had a nice three-

Above: The FAA Station in 1975 from across the valley. Darrell Chaffin and his wife

Yule ran the station like a close-

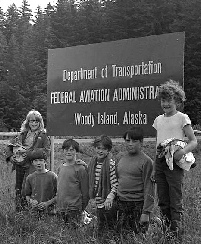

Left: campers pose in front of the official FAA sign the year the station closed down.

Right:The Fedair IV was the ferry between the FAA station and Kodiak, making several trips a day for the years that the station was in operation. Passengers would sit on benches in the little box on the stern of the boat, to stay out of the weather. All high school students who lived on Woody Island took this boat twice daily as their school bus! The boat also made yearly trips to an unmanned FAA station at the south end of Kodiak Island. For many years, Bill Torsen, whose wife Beryl was a frequent camp cook, was the operator of the Fedair IV.

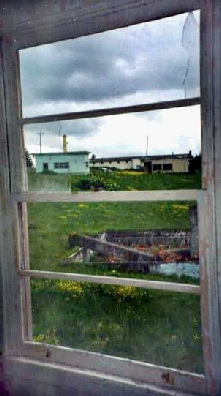

Left: The remains of the FAA Station, viewed through the window of the surviving apartment building, in 1996 after a fire in a windstorm burned down most of the station. The burned foundation of the other apartment building is in the foreground. The school to the right had a collapsing roof, but the building I took this photo from was sturdy, with minimal damage, and could have been restored.

Top: The FAA Station hillside as it looked in the summer of 2005, a grassy hill where once a thriving village and vital navigation center stood.

The Federal Aviation Administration maintained a large remote navigation station on Woody Island since the war years, and housed the workers and their families in a village of apartments, residences, a recreation hall, school, and firehouse. It was located on the opposite side of Woody Island, and they were the ones who provided the dock and the roads for camp use. In the early 1970’s, the FAA station closed down, replaced by automated machinery that could be serviced periodically by technicians who lived in Kodiak. The trend had been coming for some time. In 1964, the three huge towers on the road to Sawmill Beach had been dismantled (we were already using the towers’ old power station, which had been dragged across the island to camp in 1961, as our chapel).

There had been times in my early childhood when the FAA station had seemed like an

intrusion on our use of the island. Hiking overland to the Natural Arch always meant

traipsing across their yards and through a fence to get to the trail. And in my mind,

the station was a modern anomaly in the midst of an otherwise “pristine” island.

My ambivalence toward them was pure prejudice on my part, and not supported by any

of the available facts (akin to the extreme Alaskan’s prejudice that a mile-

My strange attitude toward the station abruptly changed in the fall of 1965, when

I had occasion to stay on Woody for a couple of months. We had to have a place to

live until the workers boarding at Baker Cottage in Ouzinkie were finished building

the new dock and store, so we remained at camp that fall. I got to ride across the

island every day in the big yellow panel van (that we later dubbed “Lurch” when camp

inherited it) and go to school in the one-

So the FAA station residents had always been the best imaginable neighbors, watching

over camp property 24/7 during the winter months, and often helping us haul or fix

things. FAA workers’ kids had frequently been enthusiastic campers. We used their

roads to get to many of our favorite beaches. So my assessment was decidedly unfair. There

was only one negative episode in the entire two-

The FAA folks crossed paths with camps on numerous occasions, such as when, about once a week, they would drive their shiny red fire truck across the island, past our buildings, down to Tanignak Lake. There they would test the pumps and hoses for awhile and then drive back to the fire hall. It kept their machinery in operation, and was fun to watch. In the summer of 1972, the few people still living at the station rented a 16mm copy of “Song of the South” to show in their rec hall, and loaned it to us for a couple of weeks thereafter. The staff saw it three or four times one weekend, and memorized most of the lines. I couldn’t stand most of the live action, but the cartoon portions were entertaining indeed. For the rest of the summer, we would quote it to each other like so many members of a secret society. “Everybody Has a Laughing Place,” said one of the songs, and that summer Brer Rabbit and Brer Bear et al provided us with our laughing place, courtesy of our friends at the FAA station.

So the station closed down, and the property and buildings became a part of the Leisnoi Alaska Natives claim. The station came to an inglorious end in the late 70’s when one of the buildings caught fire in a raging windstorm. The wind was in just the wrong direction, and when the smoke cleared, seven buildings had burned, leaving only one of the apartment buildings, the school, one house, the crumbling “rec hall” and one transmission building still standing. All but one of those cute little houses on the cliff were destroyed. Then by 2005, the entire hillside had been leveled, leaving only a dilapidated machine shop halfway up the hill to indicate that there had ever been something there. I found the site to be a profoundly sad place, and the former residents of the FAA village that I talk to refuse to even visit it. For them, and for me, it’s like a grave site. Thankfully, we have historic photos like the ones posted here, and a lot of memories of good neighbors and good times.

Some (Unusual) 1970’s Camp Traditions:

I know that one day soon a song shall rise, You’ll hear it with the sleep still in

your eyes, You’ll waken to a brand-

Try Sleeping Through This! (Music to Wake Up To)

Throughout my time on staff at Camp Woody, I was responsible for waking up the campers.

In a tradition begun by my Dad in the 1960s, I would string up a couple of dilapidated

old movie projector speakers to an old tube amp and pump music through them as loudly

as the old equipment would bear. As annoying as this probably was, regular campers

still found this to be a favorite feature of each day. I’d always begin with the

old Seekers song, “Come the Day,” with its driving 12-

I also used the Wilson McKinley’s “I Know the Lord Laid His Hands on Me” and Andrae Crouch’s “I Didn’t Think It Could Be (Until it Happened To Me!)” Various (noisy) oldies, plus oddities such as the bagpipes version of “Amazing Grace” or Dad’s theater organ version of “When the Saints” would creep in to the mix, partly because Dad’s choices in the early days were often so perversely effective at waking people up.

Nothing I would ever play was nearly as likely to arouse such murderous annoyance as Dad’s xylophone record of the “Glory March” or his dreadful pipe organ and bird calls record. Yecch! Later in the 70’s, as Christian Rock became more available, I’d regularly throw in One Truth’s “We Have a Reason to Rejoice” or Love Song’s “Don’t You Know.” But I’d always close with a quieter number like Cat Stevens’ version of “Morning Has Broken” or One Truth’s “Beautiful Savior.”

Our ultimate auditory experiment, however, was when Kelly and I linked all available speakers and amps, propped them up outside the camp kitchen facing across the lagoon, and played the Byrds’ “Turn! Turn! Turn!” for Kodiak on July 4, 1976. Several people walking on the beach below the Mission, miles away across the water, heard the music as though out of thin air!

The “Boner” Awards (No Kidding!)

The “boner” awards had to have been one of the weirdest traditions at Camp Woody,

dating from its earliest days. We shall please ignore any double meanings; we are

referring to an actual cow bone here. Perhaps it was the product of an age that was

both more innocent and more edgy than today, as we’ll shortly see. The awards were

held at the end of the noon meal, and usually emceed by my mom, Joyce Smith. he would

take nominations for the stupidest or funniest mistake or accident of the previous

24 hours (called a “boner”), and then everyone would vote for the favorite “boner.” It

was really just a popularity contest, and certainly not as vicious as it sounds. The

infractions were typical boo boos: dropping something, falling out of bed, falling

in plain view of anyone, general clumsiness, slips of the tongue, and the like. Debbie

says her award was when she had her sweatshirt under her as she sat at the camp benches,

and nearly tripped over it when she tried to get up. Not an earth-

The recipients of the award from each day at camp had to compete with each other

for “Boner of the Week,” which meant that you got to have a skull of your own, inscribed

with black felt marker, memorializing your name, camp and year. Marianne Boko was

our best calligrapher, and usually did the honors. The skulls were never in short

supply, because there were always a variety of dead animals whose picked-

Although this ceremony was funny and popular (or at least expected), the tradition

died out by the late 70’s, and will not be revived, I’m sure. In today’s self-

Legendary hospitality! Top to Bottom: The Chaffin’s cabin and guest house from below;

the view of Garraboon Point from their cabin window; The 1975 camp staff poses in

front of the Chaffin’s fireplace (Back L-

It is late June, the only practical time to put together a Senior High camp, since so many of us have to work when the cannery season starts up. The campers have just gone home, and the staff has spent the day cleaning the place and catching our wits as we gear up for the next round of campers. We’re exhausted as usual, but tonight we are in for a special treat: we’ve all been invited to the Chaffin’s cabin for cookies and cocoa. And it’s all ours for a song. Darrell and Yule love to hear the campers sing, and Kelly and I are almost relatives; they’ve known us all our lives. We all hike up the hill and over the ridge to the lovely cabin on the edge of the cliff beside Una Lake. We clamber into the snug little cabin and notice the spectacular view of Garraboon Point out one window and Chiniak Bay and the mountains behind the Coast Guard base out the other window. What a place to live!

The Chaffins are legendary hosts. Yule is a great cook, and has a huge platter of cookies on the round table in front of the windows. A big pot of hot cocoa is steaming on the oil stove in the opposite corner. It’s too warm in the cabin to light the modern orange metal fireplace which graces another corner of the room. There are songs to be sung, and I think Yule has slipped a tape recorder out onto the table. Kelly and I try for a few of our more countrified songs, knowing Yule’s love of Nashville balladeers. I can do a few Johnny Cash numbers, and even Merle Haggard, but have a hard time hitting the low notes on “Why Me, Lord?” which I’ve tried to learn from the neatly typed words she’s provided. After awhile we stop singing, because cookies and cocoa beckon, but more because talking with Darrell and Yule is at least as interesting as any song we could sing.

Yule has done everything. She has been a flight trainer for fighter pilots in World War II, a school teacher, an amateur naturalist, a fabulous photographer, and most recently, an author. Before we leave tonight, she will sign complementary copies of her Koniag to King Crab book on Kodiak and Woody history. The book features five photos taken by “young Timmy Smith of Ouzinkie,” so I’m pretty proud of it, too. She has a wealth of stored knowledge about local history and customs, and seems to know almost everyone of consequence in the Kodiak area. The out of state camp staff members pepper her with questions about life in this beautiful corner of Alaska, and I always hear something I never knew before. Yule is sporting a new metal hip, without which she would be unable to get around her beloved Woody. She sports a slight limp, but has had only a little trouble getting down the hill to pick a few flowers for her table.

Darrell is less talkative, especially in the crowd we’ve made. But soon he shares his own stories of the building of the FAA station, their own experiences when they moved to Alaska after the War (and first stayed in one of the buildings now known as Camp Woody) and his adventures as a skilled hunter. He is not one to brag or stretch the truth, but I know that he has his own share of magnificent Dall Sheep, bagged on some remote mountainside on the Alaska mainland. He and Dad soon get into a conversation involving skiffs and outboard motors and which vessels have been using his crab pot storage services lately. Darrell seems to know almost every skipper out there, with a story about every one. Except that unlike some of the local storytellers, Darrell knows how to keep some things in confidence, and I never hear him say a contrary word about anyone. Neither does Yule. It just isn’t their way.

When we first walked in the door, Darrell had politely put out one of his trademark cigars, but the scent still lingered as we gathered in the cabin. Some people hate cigar smoke, but not me. For the rest of my days, a whiff of cigar smoke will whisk me back to that cabin and the wonderful experiences I’ve shared there. And as we walk back toward camp in the orange twilight of a late summer evening, I realize that it’s the people we care about that make a place like Woody Island so spectacularly beautiful. I’ve seen Woody Island alone, many times, and I’ve always been charmed by its amazing diversity of beauty. But when you’re surrounded by loved ones, the place just seems that much more beautiful, almost as if we begin to see it through their eyes as well as our own. A visit with the Chaffins always gives me the same sensation, of seeing the island afresh through their eyes, and of somehow imparting my love for the island to them as well. Darrell and Yule are surely kindred souls on this awesome island (Continued below…).

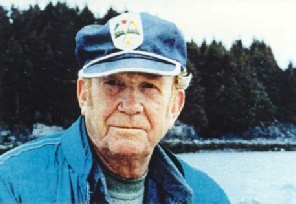

Left: Yule Chaffin, Alaskan writer and authority on Woody Island history, at her table in the cabin on Woody, in the summer of 1975. Right: A portrait of Darrell Chaffin in action, in this printer copy of a photo taken by Yule sometime in the early 1970’s. She always called him “Red.”

The author poses with Darrell and Yule outside their winter home in Smartville, California, in 1975. They helped pay for Dad to come to my college graduation in 1976, and let Debbie and me stay in this house on a bluff above the Yuba River for part of our honeymoon in 1977. Yule was my mentor for both photography and writing, and helped get me started by publishing five of my photos in her book, Koniag to King Crab, while I was still in grade school.

Famous Chaffin Hospitality

Memorable Visits With Darrell and Yule Chaffin (The Best Neighbors Ever)

Over the years, the Smith family and the rest of the staff at Camp Woody had a very special relationship with our neighbors on the island, Darrell and Yule Chaffin. Darrell retired from the FAA in 1967, and he and Yule built a charming log cabin on the bluff, trading a small plot of Mission property for a few head of cattle he had roaming the island. By the 1970’s, Darrell and Yule have a nice spread in Smartville, in the California mining country, where they spent the winter. But come spring, they would return to Woody, and spend as much time there as they could. Both Darrell and Yule are gone now, but their daughter, Trisha, still maintains and uses their lovely log cabin on the bluff. (Continued below…)

A montage of “Boner” awards clockwise from top: the author (Tim Smith), Oscar the Camp Dog (obviously a gag photo), Debbie Sullens, Travis North. The proud winner (?) would wear the large bone for an hour, and then have to wear the one worn by Debbie until the next day’s “award” ceremony.

“Persecution” in the Barn (The Underground Church Service)

Camp Woody in the 1970’s was deep in the era of the Cold War, and many of the people we knew (Nina Gilbreath, for example) had actually escaped Communist persecution. We also heard stories of the “Underground Church” (persecuted and in hiding) in Iron Curtain countries, and some of those anecdotes would show up in sermons or lessons from time to time. Around 1971, the staff began a new tradition, to help us understand what it was like for many of our fellow believers across the world. It was known as the Underground Church service, and it would take place in the Mission’s barn.

The service would typically begin in the chapel, with scriptures about standing firm for Jesus, and testimonies from the book of Acts about Christians who faced persecution. Then the cabin groups would be dismissed to go to the barn by twos and threes, quietly. Once everyone was in the barn, we would read more scripture (by flashlight, with the sliding door shut) and then pray for the persecuted church.

Suddenly the end door would burst open, and several men dressed in dark clothing would rush in and take away anyone who looked like a leader (planned in advance, of course). A makeshift drama would result, with Dad calling to us, “Stay true to Jesus!” and his captor shouting, “Shut up, you old fool!” or something equally dramatic. When the leaders had been whisked away, one of the remaining staff members would quickly explain that it was only a drama and that everyone was safe. Then that person would ask the campers what they would have done if this were a real persecution. Would they know enough of God’s Word to be able to stand for the truth without a leader? Would they be strong enough to remain true to Jesus even if it meant arrest and persecution? It was tough medicine, and sometimes perhaps too zealously acted by some of the Navy and Coast Guard men we got to do the abducting. But no one who experienced an Underground Church service was likely to forget it, or its underlying lesson.

After the drama was over, the “bad guys” and the abducted ones would return to the barn, to reassure the campers. Then the cabin groups would go back to their cabins to discuss the service in their devotions and to get ready for bed. It is supposedly a different world now, and I’m sure such services would not be popular today in the Christian community. But our purpose was to make the plight of persecuted Christians real to the campers, and it certainly did that. In our world today, the Iron Curtain is down in many places, but China, Viet Nam, Sudan, Nigeria, Indonesia and most of the Arab world are not hospitable to the Gospel and in fact are persecuting believers as I write this. It is one of the perpetually neglected stories in today’s media, and therefore, even some of us in the church are equally uninformed. So a little reminding is always appropriate. One of the songs I sang in the 70’s ended with a verse that said:

So two by two and three by three they walked in His footsteps on that Gospel Road.

And they would die in prisons and in lion’s dens, they would die on crosses and on spears of men,

But when one fell back, two more would start again to walk upon that Gospel Road!

The Mission barn as it looked in 1970. The building was still there when I visited in 2012, and was being used to cure the lumber that is cut at the camp sawmill. It is one of the few surviving World War II warehouses in the Kodiak Island area.

It was used in the early days of camp as the chapel, then as a site for skits and rainy day activities. The barn was also the site of the Underground Church services that were held for the older campers. (Travis North photo)

Woody Island, with little Bird Island in the foreground and Long Island beyond, as seen through the Plexiglas copilot window of a Grumman Goose. Camp Woody occupies a land grant (owned by the Kodiak Baptist Mission) of over a third of the island.

Conclusion: I hope my random recollections have brought back some pleasant memories for you. I’d love to hear from you if you have your own Camp Woody story. For a diary of the 1970’s, please see the series “Camp Woody 70’s Year By Year” by clicking on the Camp Woody logo below.

Click one of the links or the Tanignak logo for many more articles.

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Get Back “Home”

Please Click on the Site Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-