Island Journey with the Evangel 12

Two Decades of Evangel Visits to Long Island (Alaska)

The Evangel Visits Long Island in the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s

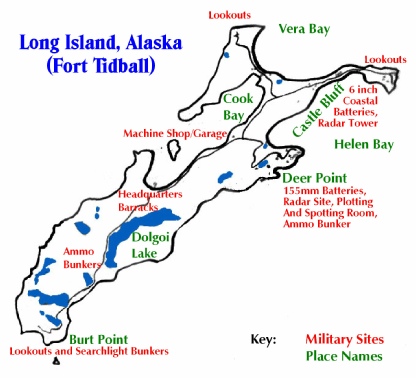

This colorized map of Long Island was created from a photo of Marianne Boko’s Camp Woody wall maps. The red letters indicate the locations and types of some of the World War II military installations. The info comes from the kadiak.org Kodiak Military History Museum site. Long Island was then known as Fort Tidball, a part of the Army’s installation at Kodiak called Fort Greely. The fort on the island was not completed until 1943, about the time the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska were taken back from the Japanese. The base was put in caretaker status in 1944 as the focus of the war left Alaska and the military focus shifted closer and closer to Japan.

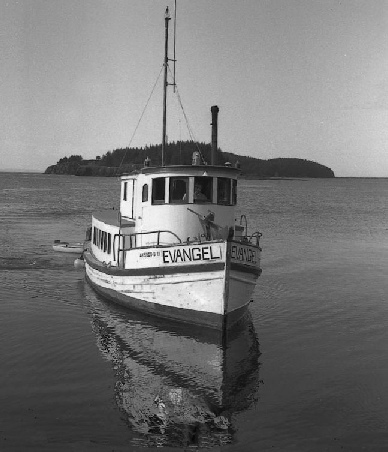

The early years: the Evangel takes a group of campers on a day trip to Long Island in the summer of 1959. The old weather monitoring hut on the Army dock is visible above the Evangel’s pilot house. Mab Boko photo.

Eight years later, after the Tidal Wave, the Evangel is at anchor near where the dock used to be in these photos from July of 1964 (taken by my sister Jerilynn). On this day, the campers stopped exploring long enough to help Kelly Smith (my brother) to celebrate his birthday. The photo on the right was taken from the window of one of the barracks, looking down at a group getting ready to eat lunch. A trip to Long Island has always meant spectacular beauty mixed with lots of old military facilities to explore.

Introduction:

When Camp Woody began on Woody Island in 1956, the staff had a lot of fond memories

of Long Island, which had been the camping site for the previous three years. Camp

Woody immediately adopted it as a great place to visit for the day. By the late

50’s, several seasons of campers had made trips to the island. In the late 60’s

it became a regular practice to take at least one camp (usually the high school kids)

over to Long Island for a day trip once a season. The Smith family often went there

for a day or two as a vacation as well, and in the mid-

An “Impossible” Tour:

This article features an account of many memorable journeys, combined into an impossible

single-

Top: The Voyager dwarfs the Evangel as they prepare to take campers to Long Island in 1975.

Right: The Evangel approaches the beach in Cook Bay, summer of 1974. This photo was the basis of a portrait that hung for years in Rev. Joyce Smith’s living room in Ouzinkie.

A Tour of Long Island (With Campers in the 1970’s)

It is late June, and the Senior High camp at Camp Woody is in full swing, with a large group of campers. I am the dean of the camp, and my parents, Rev. and Mrs. Norman Smith, are the caretakers, as they have been for every summer since the camp opened in 1956. The weather looks good, so we are heading to Long Island for the day. We load up the Evangel with enough food to serve all of us lunch and dinner. We don’t want to take two trips, so we enlist the assistance of Bill Torsen, the husband of our camp cook, Beryl, the owner of the Voyager and longtime friend of camp, who will transport campers as well. The staff and campers are eager to go; this is one of the highlights of the summer for many of us. We soon leave the dock at Woody and swing wide around the rocks and kelp beds that lie off Crab Lagoon and Sawmill Beach. Our destination is Cook Bay on Long Island, a natural harbor with a deep channel once used by large vessels in the war. In fact, Long Island is like one big fort, with military paraphernalia scattered through the trees and along the cliffs from one end to the other. It is also home to hundreds of nesting bald eagles, and has been stocked with deer. Whether history lover, nature buff or in the mood for basking on the beach, all with no one to disturb you, Long Island surely has it all.

The Center (“Headquarters” Barracks Complex, South End of Cook Bay)

The south end of Cook bay is basically the geographical center of Long Island, and

that is where the camps were held from 1953 to 1955. There is a complex of several

large barracks buildings (the same model as the main Camp Woody building) and a large

mess hall, and all were in usable condition in the 50’s but are pretty beat up by

the mid-

After a journey more than twice as long as the trip from Woody to Kodiak, the Evangel and the Voyager reach the island. Voyager drops anchor at the south end of Cook Bay. With a much more shallow draft, the Evangel can come right up to the beach, where all the supplies are quickly transferred to the skiff and brought to shore. The Voyager’s skiff has also arrived, and soon all of us are gathering on the wide lawn between the crumbling barracks. We have a quick lunch and then I instruct the campers when to return for supper I also outline the day’s possible activities, and warn everyone to go out in groups of twos or threes because some of the old military structures can be hazardous if you don’t know what you’re doing. A large group of campers head off with Larry Le Doux and me, because we are Long Island junkies, and love being tour guides.

Left photo: Campers walk along the remains of a foundation with an old barracks in the background. For many years, the island was scrounged for lumber (like half of this building) or simply vandalized. Right photo: the building in the foreground has been burned, leaving the remains of its furnace and chimneys behind.

A secret of Long Island, now removed in the toxic cleanup undertaken in later years: in 1975 Larry Le Doux and Kelly Smith inspect the huge underground fuel dump located near the main barracks area. Kadiak.org has maps detailing how many gallons of fuel each tank could hold.

Exploring the North End of Long Island

We take off hiking as soon as lunch digestion permits. No need to worry about daylight; it’s summer in Alaska, and we’ll have good sunshine until late evening. The road to the north end is long gone, a victim of the subsidence which accompanied the Great Alaskan Earthquake of 1964. So we make our way over the rocky beach until we reach the old machine shop area. The building is barely standing, but the painted outline of where the tools once hung is still visible on one wall, and the huge garage doors still hang precariously.

The old machine shop stands amid logs swept in by the Tidal Wave in this 1975 photo. Only a concrete slab remains today. Here the Army road divides to go to Castle Bluff (left) and Deer Point (right). The logs are all a side effect of the 1964 Tidal Wave.

Here is where the old road divides: the road to the left goes off through deep forest

toward the Castle Bluff installation, and the road to the right will circle up the

cliff to the Deer Point complex. We opt for the Castle Bluff road first, always a

crowd pleaser. I have brought a flashlight this time. That end of the island is

pretty boring (or downright dangerous) without one. For a while there’s nothing but

a small generator shed off to the right, and lots of trees. The road has a fine,

fur-

Lots of Quonset huts! Left: in 1968, my sister Robin stands outside a building that still had toilet paper for the commodes and still had sinks that could work. Right: a small group of huts and “skid shacks”above the machine shop is typical of installations all across the island.

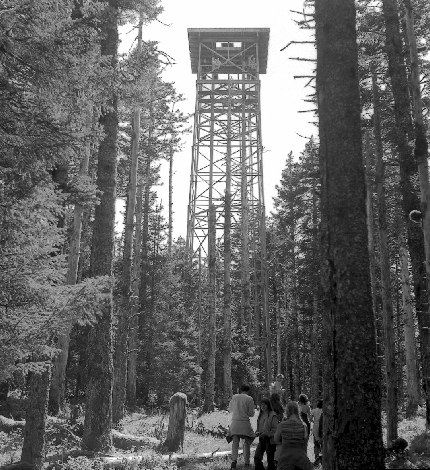

The Radar Tower at Castle Bluff:

Suddenly, through the trees ahead of us peeks the unmistakable outline of a metal

tower. It is the main radar tower of Fort Tidball, with its huge antenna still perched

precariously on its wooden roof. Climbing the tower is a no-

The Castle Bluff radar tower can be found by taking a right turn about halfway from the machine shop to the gun emplacement. This 1973 photo shows its full height. It is now mostly obscured by the spruce forest that has grown up around it.

Two photos from 1975: Debbie Sullens nears the top of the long ladder, and the tower (with Kelly Smith looking down) still shows a visible radar antenna.

Larry takes us to a secret Quonset hut just to the south of the tower, hidden in

the trees. That hut has specially decorated Masonite walls (posted in the “Castle

Bluff” link above). I get Oscar, the Smith family’s dog and Camp Woody mascot, to

pose, with appropriate tongue hanging out, before moving on. A short walk through

moss-

Two photos from 1973: Earthquake damage to the Castle Bluff section of Long Island was severe. Left: Note the cracked land along the bluff and the tilted trees. Right:The great 1964 quake knocked down the lookout tower, which had wooden timbers, unlike the radar tower.

The Coastal Battery at Castle Bluff:

But the biggest prize of our sightseeing is still to come: the huge, two story gun

emplacement of Castle Bluff, with its enormous iron gun housings. The six-

These two images of Castle Bluff’s six-

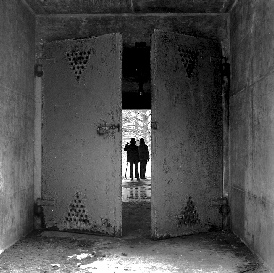

Left: the upper hallway with ammo locker doors open and stalactites hanging from

the ceiling. Right: the lower entrance (which we exit from in the text) as it looked

in 1968. Robin, Kelly and Joyce Smith emerge from the two-

We are now deep inside the two-

Still in the hallway, we turn right through metal blast doors into a very conventional-

Beyond Castle Bluff the road once dipped across a narrow spit and up the hill to

a complex of lookouts and Quonset huts. The lookouts are concrete, and will be there

forever, but the huts have all collapsed, not having any shelter from the elements.

Even worse, the Tidal Wave washed out the road, necessitating a hard rock climb

to the top. Having done that a couple of years ago for the reward of a long hike

through pushki to view lookouts that are easily found elsewhere on the island, I

forego that option. We all decide to go up the hill on the other side of the bay

to Deer Point, where more cool World War II reminders await us. We head back down

the road, briefly exploring an ammunition dump with two inner chambers and a drive

through entrance, guarded at each end by rusting orange-

Left: The north entrance to the Castle Bluff drive-

Right: The south entrance to the Castle Bluff drive-

The photos show the drive-

The Deer Point Installation:

Turning a corner in the road, we see a pretty little lily pond, and beyond it one

of the more spectacular ammunition bunkers. It’s perhaps the largest one on the island,

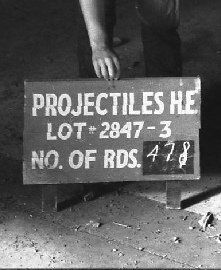

and it’s certainly the driest. It even has some wooden signs designating what kind

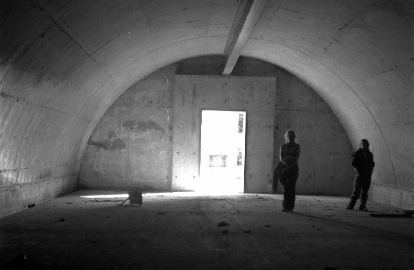

of ammo was stored there. We enjoy the spectacular echo of the half-

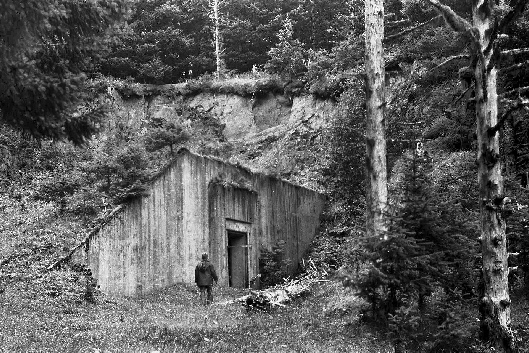

The Deer Point ammunition bunker as it looked in 1967. This photo is now historic: the bunker is now completely hidden by the spruce trees, and the seedlings seen growing along its roof line are forty feet high! It would be hard to find even from 50 feet away!

Left: in 1969, the inside of the above bunker had a sign describing the type and amount of ammunition stored. Right: the interior of that bunker (note the sign on the floor), taken from the back wall in 1973.

The Spotting and Plotting Bunker and Deer Point Radar Site

We could go back to the road and continue up to the antiaircraft gun emplacement

at the top of the cliff, but I have something else in mind. The real secret of this

end of the island is up a little gravel road to the right of the bunker. There we

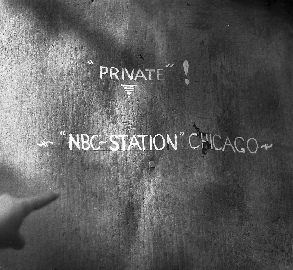

find a wooden building built of 2 x 12 planks nailed together. The foot-

Up an escarpment of loose slate rock there are even more surprises. There is a building

half-

The Deer Point radar station door as it looked in 1974. The door artwork no longer survives.

One more fine mystery awaits us now that we’re on the crest of the hill. Ahead of

us is a crumbling wooden hut, again not seemingly built to Army specs. This one has

bare wood walls inside, like one of the many storage buildings, but has been painted

two-

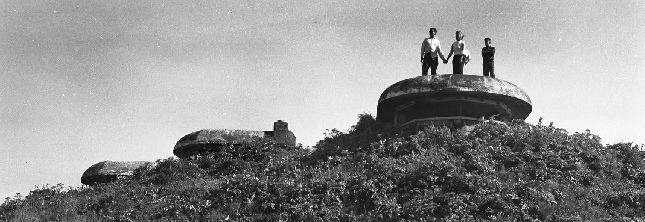

Campers explore one of the four Panama-

The Deer Point 155 mm Coastal Battery:

The rest of Deer Point is almost anticlimactic. We break out of the forest into the open to see the rings of four 155 mm coastal defense guns (which had been on what is called “Panama mounts”). These were the first guns to be operational on Long Island, because they were fairly portable and easy to set up. There’s a lookout on the bluff above the gun rings, and as we backtrack down the road we bypassed on our secret journey, we pass two large metal ammunition bunkers. Their two steel tube entries look like two rusted tailpipes sticking out from under some gigantic sedan. Around the corner, the road hugs the cliff side, revealing a spectacular view of the other side of the bay, including the guns at Castle Bluff and the radar tower above the trees.

On the way downhill, we explore a recreation hall, the only one positively identified

on the island. It is a big open room, with a nice wooden chair guard all around

it, and un-

South to Burt Point:

It’s a long hike back down the hill and on to the supper area at the end of Cook

Bay, and exploring the south end of the island would normally have to wait for another

day. But since this is a virtual tour, for the sake of the story, I am of invincible

stamina and will take you south as well! The south end has charms of its own. There

are no large gun emplacements at all on the south end, but there are many lookout

pillboxes and bunkers, that once housed huge searchlights and were armed with 50mm

machine guns as well. It also is a very pretty hike through some spectacular parts

of the island. So off we go, south on the grassy road behind the barracks, past a

cute little log cabin that was probably built for officers’ use (and left un-

Soon we pass Dolgoi Lake, the largest on the island, which was once the fort’s primary

water supply. Pipes still protrude out of the concrete near the shoreline, where

the pumping station once stood. At the far end of Dolgoi Lake, to the left as you

continue south, are two features that you could almost miss if you weren’t looking

for them. Amid a small forest of pushki plants, and covered with them as well, are

two of those giant ammunition depots, similar to the one that’s near the command

station at Deer Point. These ones are much closer to the cliffs they were blasted

out of, and without close inspection, just look like irregular hillsides. The closest

one to the lake is a sentimental favorite of mine, not because it looks any different,

but because it has been a recording site for several years. Several times now, I

have gone to this bunker and sang a few songs into my portable cassette recorder,

and was very pleased with the results. One year I brought my guitar and a whole bunch

of campers to this very bunker for the purpose of making use of its cathedral-

The “music bunker” south of Dolgoi Lake, its rusting orange-

There’s a long hike through the forest beyond the bunkers, but its military sparseness

would fool you. For up to the left, high on the ridge, is a marvelous two-

Suddenly the road takes a sharp turn to the left, and in front of us is the open

ocean of the Gulf of Alaska and Chiniak Bay. To the side of the road is the remains

of a large barbed-

Left: The double-

I cross the log-

1969 photo, right. By 2005, only one wall remained standing

Finally we reach the main part of the south end, called Burt Point. It’s an encampment of well preserved Quonset huts and support buildings in a little valley, with lookouts and searchlight bunkers on the cliffs above. Everything is rusty, and a few buildings have succumbed to a falling tree, but the south end facilities are in the best condition of any on the island, because the south end is more sheltered. The buildings are in a hollow with hills on all sides, and spruce trees all around. There have also been fewer visitors, and less vandalism and scrounging. It is typical in the 60’s and 70’s to find a building with the windows intact, light bulbs in the sockets, and with doors that still close and latch. There’s a “frozen in time” aspect to the south end.

Left: Burt Point Officers’ Quarters, 1975 photo.

The “business end” of Burt Point: one of several searchlight bunkers, which also housed 55 mm machine guns. Here one still has the wooden covering (left) and two intact inner doors (right). 1976 photos

Secrets and Splendor:

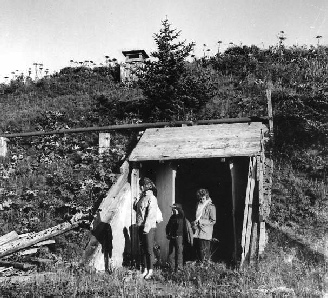

The south end is not without its secrets. In hiking through one of the little valleys on the west side of the island, south of Cook Bay, I once encountered a hidden installation. It was a security outpost, with a little guard shack high on the hill overlooking the valley, with a couple of almost perfect Quonset huts nestled in the trees on the valley floor. The guard shack even had a rifle rack for the army sentries’ carbines. It never had a good view of the ocean, so it must have been there to guard the valley itself.

Right: The interior of the hidden guardhouse, 1976 photo.The large tree outside would have afforded even more camouflage in the war years.

Since this is a simulated journey, I’ll take you on the most strenuous route back to Cook Bay: the overland route along the western edge of Long Island. There’s a pretty little lake just about opposite the Natural Arch on Woody Island, and the remains of a pump house on the south side. The shoreline near that lake has been identified as an Alutiiq archaeological site. From the lake back to the barracks complex there is not one sign of military activity. That side of the island faces the Woody channel, and there are lookouts galore at either end of the island. The hike is considerably more difficult than following the Army road, because the west end of the island seems to be nothing but those spectacular cliffs and valleys that make Long Island so picturesque from the water. I’m almost exhausted when I finally climb the last hill and see the bay far below me in the distance. But I have found some absolutely spectacular scenery. If there were no military remains on Long Island, it still would be one of the more spectacular sites for sheer natural beauty in the Kodiak area. I return to the others at Cook Bay tired, hungry and exhilarated. Something about Long Island brings out the energy and excitement in anyone who loves the great outdoors.

I never found any military remains on the southwest coast of Long Island, but it has some of the most spectacular views. Left: a photo from the highest cliff south of Cook Bay, looking north. The flats where the headquarters barracks stand and Cook Bay beyond it are visible on the top right. 1976 photo

The Evangel Departs:

We wearily pack our things up and head back to camp in the twilight. The Evangel

heads south, through the Woody-

Left: The Evangel with campers and their gear, on a clear morning in the summer of 1975. From a color print, photographer unknown.

The little “punt” in the background was an almost completely worthless vessel if any freight needed ferrying or if the weather was bad. Dad actually fell out of it once near the Woody Island dock, and walked to shore on the bottom until he could wade to shore!

Right: The Evangel, same beach, but late in the evening in the summer of 1976. From

a print, photographer unknown. It’s hard to tell if the campers are coming or going

in these photos, but the photos are of Long Island, and they’re both pretty shots,

so here they are. 1976 was the last year of the Evangel’s regular involvement with

Camp Woody, except to take Debbie and me from Woody Island to Kodiak on our wedding

day. But a lot of campers were glad for the return of the Evangel (1973 -

Epilogue For Long Island:

A hundred years from now, all traces of the wooden buildings will be gone except for an occasional set of concrete pilings. The Quonset huts will each be an indecipherable pile of rust, as some of them are already. Someday, very little will remain of the once mighty Fort Tidball. But the bunkers will still rest peacefully in their hillsides, their great doors forever open, and the eagles will still soar above the cliffs and nest in the trees beside crumbling lookout pillboxes. The bright waters of the lakes and ponds will reflect the dark green spruce trees. The waves will still crash beneath Castle Bluff. And people will probably be captivated, as I always will, by the island fortress that nature has reclaimed. Long Island is truly one of Alaska’s great treasures.

The sun sets over the “Three Sisters” Mountains in this colorized photo taken from the top of the radar tower at Castle Bluff, Fort Tidball, Long Island, Alaska. 1972 photo.

Goodbye From Historic Fort Tidball.

To Get Back “Home”

Please Click on the Site Logo Below:

To Return to the Woody and Long Island Index,

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

Woody / Long Island Index Long Island Center to Burt Point

Long Island Deer Point Long Island Castle Bluff

Information from this site can be used for non-