Evangel Island Journey 8 -

The Evangel’s Journeys to Port Wakefield, Afognak, and Port Williams

By Timothy Smith (revised in 2020)

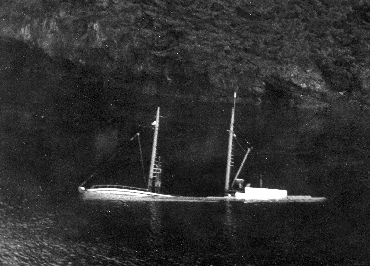

The Evangel lies at anchor in Danger Bay on Afognak Island in the late spring of 1951. Notice the abundant Sitka spruce trees of the northeast end of Kodiak Island and its surrounding islands.

Author’s Note: This article features many of the north-

A Visit to Port Wakefield (via Whale Pass)

It is late spring, 1960. The Evangel has already visited several villages on the South End. As we leave our home port of Ouzinkie and head northwest toward Port Wakefield cannery, we venture into the much more challenging waters that lie between us and our next destination. While Shelikof Strait can kick up horrendous swells and blow a gale like it’s a wind tunnel, our journey will take us though “Whale Pass” (Whale Passage on the maps) and up the shallow end of Raspberry Strait. The journey between the islands and up the narrow channels will involve some of the trickiest navigation, and careful coordination with the tides. Our goal is Port Wakefield, a pioneering king crab processing plant which has its own village (and even a school). Now that we live in Ouzinkie, we are much closer, and can visit more often.

Located near the middle of the northeastern shore of Raspberry Island, Port Wakefield

is normally accessible only from the northern end, but we are not coming in that

way. The south end of Raspberry Strait, which is very shallow in places, is impassible

for most of the larger boats. But the Evangel has a shallow draft, and Dad knows

how high the tide needs to be to get through. In this way we avoid the much longer

trip around the north end of Raspberry Island, which would mean going northwest up

Kupreonoff Strait and making the turn. That would add many hours of travel for us.

The Evangel is slow enough as it is! But Dad knows the islands well, is a careful

navigator, and has a well-

We have timed our travel so that our journey through Whale Pass (called Whale Passage

on the charts) is as close to high tide as possible. Like Scylla and Charybdis in

The Odyssey, Whale Pass has a reputation for trouble and tragedy. It is a place where

the protected waters of Marmot Bay face the turbulent waters of Shelikof Strait,

and the meeting is never pretty. Due to the peculiarities of tide, there is a different

water level between the two ocean bodies, which is exacerbated when the tide is turning. We

are heading into a reef-

I snapped this photo in 1968 from the window of a Kodiak Airways Widgeon. The boat had hit the tide wrong, and the current had swept it into one of the submerged reefs in Whale Pass.

As a school child in Ouzinkie, I soon learned that almost everyone knew someone who had died in Whale Pass, and many had lost relatives there. It was an especially dangerous place for crab boats with stacks of empty crab pots on deck, and for salmon seiners with holds full of fish, heading toward nearby canneries at Port Bailey or Ouzinkie.

We approach Whale Pass cautiously, scanning the water for any sign of trouble. Soon

ahead of us is a little wall of water about six inches high, which signals the edge

of a large whirlpool. As we enter the whirlpool, Dad tries to feel how the vessel

is reacting to the turbulence. The boat begins to pivot on an invisible axis, and

Dad spins the wheel rapidly to compensate, the chains rattling in the pilot house

bulkhead. Just as quickly, the boat reaches the other side of the whirlpool, and

again the 25-

We know many boats have been lost here; ours will not be one of them. Suddenly we burst as out of a cocoon into the calm waters of Marmot Bay. I take a quick peek out the side door toward the stern at the foaming water fading behind in our wake, amazed at such raw natural power. Experience is the best cure for white knuckles, and we immediately resume normal progress as though nothing out of the ordinary has happened. Actually, it has been just an ordinary trip through Whale Pass. Dad throttles back, hands the wheel to me for a few minutes, and heads below to make a cup of coffee. Our own private roller coaster ride is over until next trip. But one more challenge lies ahead.

It is a little past high tide as we reach the southern end of Raspberry Strait and turn northwest toward Port Wakefield. I scurry out to the bow and look down, something I always do when we come through here. The sand in the area is occasionally of a lighter color than in most places around the islands, and off and on I can see the dim shapes of the sandbar just a few feet below the keel. Then I suddenly see much clearer patches of light sand, and the Evangel goes bump bump for a couple of seconds, but the water soon goes dark again. Larger boats with deeper draft have no choice but to go all the way up Kupreonoff Strait and come down the deeper end of Raspberry Strait, no matter how high the tide may be. A little later in the tide cycle and we might have had some trouble, but Dad has timed it correctly, and we will be tying up at Port Wakefield shortly. Dad is by no means foolhardy; our successful journey is the result of cautious experience. (Continued below…)

Top: Port Wakefield from the pilot house of the Evangel, a little bit of the bell clapper is visible. Above: a photo from Yule Chaffin’s 1962 book, Alaska’s Kodiak Island shows a family playing on the beach, and the floatplane the photographer flew in on tied up just down the beach. (Book scan used with permission of the Chaffin estate)

Port Wakefield is a place of pleasant company and old friends, and many of the people who work there and live in the little village have been very receptive to the ministry. In fact, Dad recently started a Sunday School in the little village, held in one of the homes, and has brought some more materials for them to use. He came over by plane last winter to preach the memorial service after two men from the cannery died in a skiff accident. And several of the village families have kids my age, so I love going there to see my own set of friends.

The cannery is a wonder, not because it looks particularly modern, but because inside,

the place has been modernized with the very latest in processing methods for the

new cash crop: king crab. We have toured the place several times, and Lowell Wakefield

gave Dad some slides of his operation the last time we came through (see the article

called “Cannery Work” for those photos). But even more amazing to me are the homes:

modern, classy, and built out of pre-

Tonight we have been invited to the home of one of the foremen for dinner. The husband and wife are originally from the Philippines, and tonight they serve me sweet and sour pork for the first time in my life. While the adults converse, I go with their son Mel to his room, where he shows me his new ukulele. He plays “Does Your Chewing Gum Lose its Flavor on the Bedpost Overnight?” and strums through all the chord changes with considerable skill. I am more than a little impressed. All I can play are a few simple songs on the piano, and this energetic singing and playing seems a lot more fun to me. (Continued below…)

Left: a bin of freshly-

The following morning, while we are making preparation to leave at the next high tide, Dad goes to “mug up” (coffee break time) signaled by a very loud clanging on the mess hall bell, which is an old acetylene tank suspended on a rope. Like always, Dad goes where the people are; a good many would never come to our little services, but will talk in a neutral setting like coffee break time. Mom goes to one of the homes to meet with some of the mothers. I amuse myself by making a fishing pole out of an old stick, and wrapping fishing line around one end, with a lure I bought in Larsen Bay. I decide today is the time to try it out. The way to pull up a fish, assuming I get one, will be to turn the stick slowly like a winch – not an effective pole by any means. I drop my line off the stern of the Evangel and wait for awhile.

Soon I feel a weight on the pole, and start the slow process of winching whatever

it is up where I can see it. Finally, I hear that the fish has broken the water,

and look down into the most wretched face God ever created! I have on my line a very

placid but horrid-

Big sister Jerilynn heads out to the stern while I stay in the galley, tentatively

listening. I can hear her laughing on the stern, although I can tell she’s trying

not to. “Uglies” are not for the faint of heart, and she sees what I saw in him immediately!

She mercifully disentangles him and I hear him splash away. She comes back into the

cabin, with a bit of a twinkle in her eye. My feeble fishing effort would only have

worked on such a dumb beast as the one I caught. Later I will realize that no self-

I later ask Jerilynn why she let the fish go (not that I am in any mood to greet him again). She will someday be a renowned physician, and is already working on her bedside manner. She explains to me that “Uglies” are so bony that it would take three or four of those things, big as he was, to fill a skillet, and that they are murderously hard to clean anyway. She is being a good sister, for with great tact, she has spared me the trouble of having to deal with a creature I’d already run away from once! As a good Alaskan boy, not much unnerves me, but the sight of that monstrous fish peering up from beneath the Port Wakefield dock is too much for today. It is not until a decade or so later, when working in a tank full of furious Dungeness crab, that I will feel such consternation at live seafood! (See the “Cannery Work” article). I quietly go out, wind my fishing line around my fancy stick pole, and put them away for another time. When the day’s business is completed and the tide is right, we are off, down Raspberry Strait without incident and on our way to Afognak. (Continued below…)

The EVANGEL at Afognak

Afognak village is the largest settlement on Afognak Island, which is itself about a third as large as Kodiak Island. The rest of the settlements are lone or two logging camps, a fish hatchery, and an occasionally operated recreation center run by the Navy at Afognak lake. It’s not long before we drop anchor at Afognak, one of the many villages with no dock. It seems to be one long, rocky beach. Dad has to pick his anchorage carefully, because there are plenty of rocks just below the surface. Once we pull up the skiff, we start out to visit our friends. We have friends in every port, so to speak, and Afognak is no exception.

We have many friends in Afognak, but there is also a Slavic Gospel Mission chapel and resident missionary in the village. My parents are on friendly terms with the local Protestant missionary, but they also don’t intrude. I’m sure they would participate if asked, or help each other in any way they could. But because of this, our visits to Afognak are usually short, a few hours on our way back to home port in Ouzinkie, and are timed not to interfere with any of the local church services.

We visit the Nelson family, who live in a newer home, a two story pink building with large windows. There is a stand of spruce trees on three sides, a dirt road out front and a great view of the beach. Betty Nelson is one of Mom’s good friends, so the teakettle gets used and they start talking. I go upstairs, which consists of a large, mostly unfurnished room left mostly to the Nelson kids, and play with them for awhile. Then somebody decides to take a walk to see a friend, and I tag along to see the sights. It’s not like I could get lost; from practically every home I see, the Evangel is clearly visible at anchor, and so I know where our skiff is, too.

Afognak was formed early in the nineteenth century, when a group of retired Russian America Company workers and their Native wives settled next to an existing Native community. Other immigrants later arrived and intermarried, creating a village with a wide diversity of surnames, and a generally upscale standard of living, judging by many of the houses. We stroll down the road and walk past the nearby Von Scheele mansion, for that’s what it looks like to me. There are no comparable structures in any of the other villages. That home and several other larger dwellings underscore that the community of Afognak’s history is different from many villages, and its present is very different as well, for Afognak has cars! It’s only a few jeeps and pickups, but it impresses me, because neither Larsen Bay (my first home) nor my home village of Ouzinkie has anything bigger than garden tractors.

It seems odd to have a large village with no dock or harbor facilities. Many of the residents work as fishermen, with nearby canneries such as the Kadiak Fisheries facility at Port Bailey. But others work in the logging industry, for there is a lumber camp and sawmill on Afognak Island, taking advantage of immense and mature forests of Sitka spruce trees. The von Scheele family has a store, and Bob Von Scheele runs the Shuyak mailboat, which was our familiar link to the outside world all winter at Larsen Bay.

I catch a glimpse of the village school, and it seems from a distance to be a near

twin of the one in Ouzinkie. It must have been a standard Bureau of Indian Affairs

design in the mid-

Down the beach is a small home with only two or three rooms on the ground floor,

a prominent “kelly-

Many other buildings are familiar to me as a life-

It is an odd feeling to look at a house from the beach and see mostly forest, and from the rear and see mostly beach and bay! This seems to be true for most of the houses. Compared to the treeless South End villages, this village is in a fairytale forest wonderland. It is one of only two villages built in the northern islands’ spruce forests, Ouzinkie being the other. The whole village seems to be one long series of houses along the road which fronts the beach, and doesn’t seem to be more than two or three houses deep at its widest point. The whole place is peaceful, inviting and picturesque, with lots of southern exposure to the sunlight all day long. Since it was once a retirement community during the days of Russian America, it is completely understandable why it was chosen for that purpose. (Continued below…)

Views of Old Afognak (1950’s)

Above: Afognak on approach from the south across Marmot Bay. Right: “Garden Beach.” Below: another view of part of the shoreline. Old Afognak was a very long village, and had roads and vehicles, which impressed me at the time, since no other village did.

Afognak Abandoned: Photos of the village since the 1964 Quake and Tidal Wave

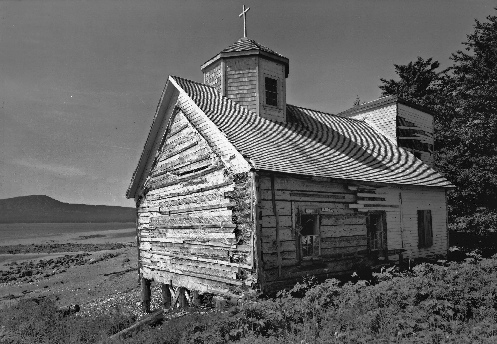

Right: Eva Inman of Port Lions poses near one of the old homes in the mid-

An Epitaph of Sorts for Afognak and Port Wakefield

When the Tidal Wave hit in March of 1964, it changed the fate of both Port Wakefield and Afognak forever. While not destroyed by the wave, the subsidence of the Kodiak Archipelago, including Afognak and Raspberry Islands, by as much as six feet, quickly made the two communities unlivable. A new site for the people of Afognak was selected, and the Lions Club, the Salvation Army and other charitable organizations donated money and materials to build a new village on higher ground. Afognak’s citizens moved to Port Lions, as they called the new village, by the end of 1964. Shortly thereafter, Wakefield Fisheries moved their operations to Port Lions as well. They built a fine new cannery in a much more accessible location, with a good dock and harbor facilities, and connected it to the new village by means of a long causeway and a new road. They moved many of the beautiful homes of manufactured logs that I had admired so much onto barges and transported them to Port Lions, where they still stand to this day. For more on Port Lions, see “How Not to Get to Port Lions,” which features a few photos of the village toward the end of that article.

In 1976, Dad took the volunteer staff from Camp Woody to visit Afognak, a memorable

journey on the restored Evangel. Before we left, (a course of events I will rue to

the end of my days) Dad and I scoured Kodiak for any black and white or color 120

film for my Yashica Mat reflex camera, and came up empty. So one of my most memorable

journeys to Afognak, in which I got to tour the devastation inflicted by the Tidal

Wave, was recorded only by the movie reel of the mind. My younger brother Kelly remembers

anchoring the Evangel offshore, and hitting a rock with the prop on the outboard

motor of the skiff, shearing the pin. Of course Dad always carried spares. I just

remember the strange panorama of tide-

The school, for example, seemed to be in a brackish field of salt water, although

it was still mostly intact. The pink Nelson home was as sturdy as the day they left,

although they or someone else had removed most of the windows. I went into both the

church and the priest’s home behind it, and found them to be in almost perfect condition.

The rectory had those steep, boat-

One more place was a standout, the Von Scheele home, which I had considered a mansion

in my childhood. It was still an impressive place, two stories, with a lovely staircase

and banister. I even looked up into the attic, and found magazines from World War

I through the late 1920’s and newspapers from San Francisco dated 1927 and 1928.

This was not a library or a hoarder’s collection, but insulation, stuffed between

the rafters. Having lived for years in a completely un-

So why was Afognak abandoned? Besides the impossibility of dealing with the intrusive

tides brought on by a six-

A Photo Gallery of Other Northern Sites

Port Vita, Mothballed Herring Plant (Raspberry Island)

I love abandoned buildings and ghost towns, and that love came from many visits to old, retired canneries such as this herring plant, Port Vita. This photo was taken from the little rowboat we kept on the deck above the main cabin, and shows the Evangel tied up to the aging pilings of Port Vita at low tide. By the time I can remember, it was no longer in operation, but we would visit with the caretakers on our way to other canneries and villages. I also have fond memories of Port Hobron (an abandoned whaling station), and Uyak Cannery opposite Harvester Island, which our family used to build the “warehouse” in Larsen Bay. The retired herring plant at Zachar Bay was actually restored and used as a modern fish processing facility many years after we stopped our island travels.

Fish and Wildlife (Dept. Of the Interior) Salmon Hatchery at Kitoi Bay, Afognak Island

Kitoi Bay, a small body of water off Izhut Bay on Afognak Island, has been a salmon

hatchery for many years. It was a favorite place for us to visit, because the scientists

working there would show us so many interesting things in their laboratories. I remember

the tanks full of salmon in various stages of development, the fish elevators that

allowed the salmon to spawn in several streams, and the lake that served as a temporary

home for the soon-

The hatchery was heavily damaged in the 1964 Tidal Wave, but was rebuilt by the Alaska Dept. Of Fish and Game. The photo shows the Evangel at anchor off one of the spawning streams in the summer of 1957 (from a very faded print). It’s a strikingly beautiful location, and it’s a shame we didn’t take more photos there.

Shuyak Island: Port Williams Cold Storage Fish Processing Plant

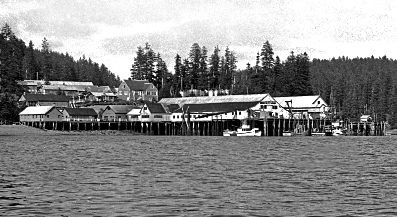

Port Williams, on Shuyak Island, the northernmost island in the Kodiak archipelago,

was one of the first cold-

Top photo: he Evangel is dwarfed by most fishing boats, but here it seems almost

a speck tied up to the Port Williams dock at the stern of a freighter in this mid-

Above: Port Williams in 1966 from the window of a taxiing Kodiak Airways Grumman

Goose. One of my vivid memories of Port Williams involved a passage through one of

the cold storage rooms to get from the shore to the face of the dock. The freezing

process involved ammonia in some capacity, and the pipes always leaked a little bit,

a real shock to a young nose such as mine! Notice the abundant spruce trees behind

the buildings, so different from canneries such as Lazy Bay and San Juan. Shuyak

Island is now a major site for State of Alaska-

“I Will Make You Fishers of Men!”

An Unusual Ministry

A few photos exist of Rev. Norman Smith, in a suit, preaching at a wedding or a funeral. Some photos show him leading worship or teaching around a campfire at Camp Woody on Woody Island, or preaching in a little village chapel. But this is the only photo of Dad just standing on the deck of someone’s seiner, coffee cup in hand, talking earnestly with one of the fishermen. It was something he did a lot, but this is the only photo of it to my knowledge. My brother Noel caught this candid shot back in the late 1950’s, and I cropped it to zero in on the conversation. This was taken at one of the northern ports of call, because in the background of the original there are tons of spruce trees on the shoreline.

My parents’ method of Christian witness was unconventional, hard for their peers in local churches to understand, and even harder for their church denominational bosses to grasp. Today we would call it “friendship evangelism,” but my folks just thought of it as going where the people are. What better starting place for a personal conversation with fishermen around the Kodiak Islands than on the deck of a fishing boat, with your boat tied up to theirs? Going to “mug up” at coffee break time in some cannery, or ordering a sandwich and soda in a bar with someone who would never join you in church seems to me to be the very essence of “Go into all the world and preach the Gospel to everyone.” It was also the very essence of the ministry of the Evangel.

The next article is “The Evangel Visits Ouzinkie in the 1950’s.”

To go back to the Evangel Index,

please click on the logo below:

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Get Back “Home”

Please Click on the Site Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-