Goose Stories (Grumman Amphibian Aircraft)

By Timothy Smith, Originally posted in 1999, latest revision in 2020

Goose Stories

Part of the “How to Get to Kodiak” series of articles

Left: an aerial shot of a Grumman Goose sent to me by Jim Klement. Right: A Grumman Goose amphibian races for the sky in this photo from the Fred Ball collection.

Introduction to the Twentieth Anniversary Edition:

It’s been over twenty years since the this article was first posted on Tanignak.com. When it was first written, the Grumman Goose was still in regular service around Kodiak Island. As one of the the first five postings on my website, the article needed a little sprucing up and revision. There was a 2011 rewrite with almost all the original text. But in 2020, the article needs some of the many photos that pilots and fans of those old Grummans have sent me since the original was written. Naturally, I had to post those wonderful photos! I hope you like this new version of an article that has prompted emails from all over the world. I’m not the only one who loves those wonderful old amphibians!

Bob Hall, founder of Kodiak Airways, in the hatch of a Grumman in the 1950’s. A more detailed article on Bob’s early days is called “More Amphibian Adventures,” also on Tanignak.com. This article is dedicated to him and to the many other Kodiak bush pilots who have passed on.

Dedication:

A landmark event in the history of Kodiak Island in the 1950’s and 1960’s is the

emergence of regular bush pilot service. But this fact alone doesn’t quite explain

just how deeply the pilots and planes became part of the lives of the remote inhabitants

of the Kodiak Island area. To this day, old timers refer to pilots by name, and

affectionately tell stories of adventures in various planes. The aircraft are called

by their alphanumeric designations, as if repeating the names of old friends. The

pilots who were part of that elite group who flew for Kodiak Airways, Harvey Flying

Service or a handful of other outfits in the early days have begun to tell their

stories, many of which can be found in this series of articles at Tanignak.com. Pilots

of those vintage Grummans can hold forth for hours about close calls, survived crashes,

the fate of every plane they ever flew, and the legacy of colleagues that have passed

on. I got to have a few phone conversations with Bob Hall, founder of Kodiak Airways,

in the years before he passed away, and I am honored to dedicate this 2020 re-

Pure Alaska!

In the summer of 1997 I was privileged to fly back to Larsen Bay, my first home,

which I had not seen since the mid 1960’s. I flew in a modern, high-

What a far cry such modern flying is from the early bush pilot era, which extended well into the 1970’s. I was a regular passenger on Kodiak Airways in the late 1960’s as a boarding student, living away from home to go to high school. Climbing in and out of various amphibious and float planes at the seaplane terminal in the Kodiak Channel was as normal as jumping on a subway is for a resident of Manhattan. But as the GPS and the smooth runway in Larsen Bay reminded me, a plane with wheels could be working anywhere. Those old Grumman amphibians were pure Alaska.

The Back Story on the Goose and Widgeon:

The Goose and Widgeon were amphibious planes developed for military use in the late

1930’s and pressed into extensive service in World War II. The military needed planes

that could search for downed Navy fliers, supply remote island outposts, and tend

to navigational, meteorological and intelligence-

The Workhorse Goose: N87U

Kodiak Airways’ workhorse Goose, N87U, delivers the mail in Ouzinkie in 1972 (Stanley Grant photo) and in 1969 (Travis North photo), and was featured in a display at the Smithsonian in 1997, where they got the paint scheme and livery mostly right. The text with the graphic reads in part:

In Alaska, where mountains and glaciers dramatically combine with picturesque bays

and inlets, commuting by air is a way of life. Coastal communities without airports

depend upon seaplanes for transportation, groceries, and supplies. Beginning with

Alaska Coastal Airlines’ purchase of a G-

In the postwar era a few Grumman amphibians were built exclusively for the civilian market. One such cushioned, curtained luxury Goose graced the Smithsonian in 1997, right below the “Spirit of St. Louis” and a replica of the Wright Brothers’ first plane. But when the projected boom in postwar aviation and especially seaplane business failed to materialize, the models were discontinued. The postwar single flight of Howard Hughes’ magnificent “Spruce Goose” seaplane, which was already outmoded before it was finished, illustrates the sudden change in the aviation industry. Grumman kept making the larger Albatross amphibian for the Navy, but turned its focus elsewhere, becoming an aerospace giant.

The Goose and Widgeon found regular use in the Caribbean and tourist places like California’s Catalina Island, but when pilots began acquiring them for use along the massive Alaskan coastline, legends were born. The planes are perfect for the remote Kodiak environment: tough, versatile and dependable. The Grumman airframes are able to survive horrendous abuse, and capable of being rebuilt even after being fairly squashed in some mishap. The article, “Runways to Remember” in this series describes a Goose that was fished out of a lake, pounded back into shape by a couple of intrepid Kodiak Airways workers, and coaxed back to Kodiak for further repairs. It is now in private hands, and features some of the most advanced electronics ever stuffed into a Goose. By the 1960’s, mechanics regularly built their own replacement parts, forming an important if unheralded closet industry dedicated to keeping the grand old birds afloat and aloft. Grumman seaplanes and spare parts were scrounged from dozens of remote sites around the planet in the effort to keep the aging equipment working, a process that continues to this day.

Organizations such as the Alaska Department of Fish and Game as well as a few bush

airlines and a dwindling cadre of well-

Kodiak Airways logos from the early and late 1960’s (from correspondence found in my Dad’s desk in Ouzinkie after he passed away).

The Early Days:

When Bob Hall started up his self-

Five decades later, the ancient Goose and its more delicately-

One of Bob Hall’s first regular visitors to Larsen Bay was a fabled Grumman Widgeon painted pink and teal, affectionately dubbed the “Easter Egg” by locals. See “More Amphibian Adventures” for more on that plane, the first one to catch my imagination as a child. On one memorable trip in it as a very young boy, I got to fly low over a Kodiak Bear. I marveled at the way the big old plane seemed to be nearly level while the world outside was tilting wildly. Centrifugal force slammed my little body into my barely padded seat cushion, and my little nose was glued to the Plexiglas as we swooped to a landing in Larsen Bay. Plane flights were rare for us in those days because Dad had the mission boat Evangel, and we almost always did our journeying by boat. (See the Evangel Voyages index for our adventures) But it was more than enough to inspire me with an awe that has never departed and an undying affection for the old plane, which remain no matter how many trips I take in a Grumman amphibian.

My family’s Goose charter ride in the summer of 1996 involved a departure from the airstrip at Ouzinkie...

A Goose Ride in the 1960’s

Traveling by Goose is no longer an everyday occurrence for Kodiak Island passengers.

The only way to recreate the ambiance of those adventurous days now is to let memory

play tricks with you and create a hybrid experience based on scores of memorable

journeys. Let’s take a trip to Ouzinkie in the pre-

I march my bag up to the counter, where Archie Zehe, legendary dispatcher for Kodiak

Airways, is talking by short-

The Kodiak Airways terminal on the Kodiak channel, taken by Travis North in 1971 as we passed by in a skiff. This photo is also featured in my article, “From Shore to Sky.” In the text of this article, I’m in the blue building getting ready to hop in a Goose. In the photo, you can clearly see the tracks of the last amphibian on the gravel ramp.

A real luggage tag ticket (hardly ever needed) and a copy of a plane ticket (on the

venerable N87U) that I found in a box of my high school things are memorabilia of

a long-

Shortly after Archie’s transmission, the marine band radio crackles with a clear

reply. The Ouzinkie storekeeper is prefacing his words during each transmission

with an “Ahh” sound to let the transmitter catch up: “Ahh, Roger, KWA26 back to

KXJ66. We got CAVU here this morning, Archie. Looks real good here. Got winds

south-

As the first one there, I happily clamber up the narrow aisle of recently reupholstered

brown and ochre seats, step over the aluminum housing for the landing gear with its

little “double-

Various switches are switched and buttons are depressed and the starters are engaged.

The big radial engines whine, cough and sputter to life in a cloud of blue smoke,

and the brakes and landing gear groan in protest as the seaplane is turned and forced

down the beach into the water. Once safely away from the ramp, the pilot busies

himself with making sure the wheels are up. This model has a little crank to make

sure the ancient hydraulics got the job done. It is one of the most dangerous parts

of the flight. As a true amphibian, landing a Goose on a runway wheels-

This ghostly-

Satisfied that the landing gear is where it belongs, the pilot turns the Goose down

the channel, pulls the yoke into his chest, gives it a half-

The plane pitches and yaws a bit as the pilot adjusts the trim and cuts back on the

throttles. It may be only a ten-

In a few short minutes the plane reaches the far end of Spruce Island. He circles

the town’s northwest fringe, swinging wide over Sourdough’s Flats and Otherside Beach

before lining himself up behind the school for his descent over the Church hill.

He made a careful note of the boats anchored in the bay as he made the first turn,

so he won’t be facing any surprises as he lands. He cuts power a little and drops

some flaps, and the plane abruptly sinks like a stone, feeling as though it will

pancake into the swamp below. He guns it and levels off; a Goose with no power is

basically a big rock. We do not actually descend over the Church hill; we find an

imaginary tube between the clump of tall spruce trees beside the store warehouse

and the trees which frame the Russian Orthodox Church to the east. At one point

in our short descent we are almost eye level with the church and are below the tops

of the trees by the store. We seem to have no more than fifty feet vertically between

the red bottom of the Goose and Mike Chernikoff’s little yellow boathouse that juts

out into the bay. To people on the trail below, the big engines have slowed to a

percussive rattle, and the big plane passes close overhead with an awe-

From my vantage point in the cockpit, I feel the engines idle, and the momentary pause as the Goose struggles to remain airborne on its own lift and momentum. Just kidding with us, the old bird resigns itself to its fate and settles down politely on the bay, again taking on the persona of a speedboat for a few seconds before the ocean wins and the plane settles off the step. Arriving at this angle means that the pilot will have to taxi for some distance to reach the broad, sandy beach behind us. The pilot is in a bit of a hurry today. If he goes too slowly to be up on the step, he will release such a wake that he is sure to disturb some of the boats in the bay. We slow down long enough to turn toward the beach, and then he guns it as though taking off again, a disconcerting feeling for the passengers since the broad side of the church hill is dead ahead. With just enough taxi room to spare, my pilot idles the plane again, and it settles like a heavy seiner into the water. As soon as we have slowed, he begins the process of dropping the landing gear, winching it into locked position with his hand crank. With a bump we hit the sand below, and the pilot guns it for all it’s worth; the Grumman Goose is a most inefficient dune buggy and must be maneuvered and steered only by the sheer force of its massive radial engines. The sand of the beach is notoriously soft in spots, and planes have been known to get stuck for awhile until assisted by the tide. This time the sand holds, and we spin noisily in a semicircle, high on the drier and more stable gravel below the church hill.

With its tail now facing the shoreline, the pilot cuts the power and the engines sputter to a stop. Even before the props have stopped turning, villagers have crowded around the plane. As the rear door opens from the inside, the pilot is greeted by first name, as warmly as Lindbergh ever was. My arrival is noted, and within minutes the entire village will know that I’m home. Not that I’m all that interesting; it’s just everybody’s hobby to know the coming and goings. The pilot begins unloading freight, and soon everyone will know who got a shipment of what. My bag is unceremoniously dumped in my arms, and the pilot states the obvious about seeing me on the return trip. I head up the trail toward home. I am almost to the front door when the roar of his engines echoes from the foothills of Mount Herman and off the mountains across the channel on the Kodiak side, before gradually fading out of earshot. It will be a few minutes before I catch my breath and feel acclimated to solid ground again.

Photos Chronicling Arrivals and Departures in Ouzinkie in the 1960’s:

Above: A Goose taxis in after landing, heading toward the sandy beach below the church hill on a flat calm day. Mount Herman rises in the background. (1968) Below: A Goose roars up onto the beach (1967, one of my favorite early photos).

Above: it turns around on the sandy beach, ready to load and unload.

Above: Goose N87U heads out into the bay in choppy seas, in for a bumpy takeoff! Meanwhile, at least one kid engages in one of our favorite things to do: to run through the backwash! (1967) Below Right: A Goose finds the tide too high to use the beach, and so has to be unloaded by skiff, 1973. Below Left: A Goose throttles up to take off from Ouzinkie bay.

Above: A historic 1974 photo. A Goose and a Cessna float plane pass each other in Ouzinkie Bay. Behind them is the Ouzinkie Seafoods cannery, which burned down to the pilings shortly thereafter. And a few years after that, Ouzinkie got a landing strip behind the village, and Goose arrivals at the long sandy beach were no more. I’m sure float planes still occasionally arrive this way, but the above photo went from daily to never in a very short time!

Now back to the story...

The Return Trip

Since I am only on a short weekend visit, I start worrying about the return trip by Sunday afternoon when clouds, light snow and a light breeze indicate that the weather is changing. Dad taps the barometer and listens to the weather report on an Anchorage station: “Shumagin Islands to the Barren Islands including Shelikoff Straight: North to northwest winds 20 to 25 knots becoming light and variable winds by morning. Snow showers and temperatures in the mid to upper 20s.” Dad shakes his head and tells me to plan to stay another day.

Monday morning dawns gray with low clouds and snow flurries. I look out the dining

room window and can’t see Prokoda Island (called “Cat Island” supposedly because

of a peculiar local form of pet euthanasia, although some say it’s because the island

resembles a reposing cat). Nice weather if it were already Christmas I suppose,

but definitely unflyable. I am “socked in”. I resign myself to enjoy the extra

day, as sad as Brer Rabbit in the briar patch, and presume the school will understand

on Tuesday. Sometimes the car-

Spray engulfs “Cat Island” in the Ouzinkie Narrows in a rare clear weather storm, 1967.

As often happens around Kodiak, Tuesday morning dawns with no memory whatsoever of

the previous bad weather. Another nearly cloudless, bright and cold winter morning.

Archie’s voice on the marine band informs us that our flight will be arriving in

Ouzinkie first, then deliver passengers and mail in the village of Port Lions and

the Kadiak Fisheries cannery of Port Bailey. I might get to class by third period

(I’m broken hearted, of course). When the plane taxis up on the beach, I note with

some irritation that the copilot seat is already taken. I slouch into one of the

seven other seats behind the cockpit bulkhead. Suddenly, the pilot turns around

and in a somewhat strained voice begins rattling off official-

We take off, deliver the mail and add a few passengers in Port Lions, and head toward

Port Bailey cannery. The inexplicable airline-

The pilot opts to return to Kodiak via the Spruce Cape route rather than the more dramatic cut through the passes behind the Navy Base, since there is a stubborn case of low fog in the pass over Buskin between Pyramid and Barometer mountains. It’s probably why he went to Port Lions first, in case that cloud cover was heading that direction. As we descend into the Kodiak channel, I look up at the high school on the hill and note ruefully that I’ve missed most of third period. (Seaplanes never land this way in Kodiak now. They would risk tangling themselves in the Near Island Bridge. When I first walked across it in 1996 and looked down at the houses and canneries, I was inexplicably disoriented, until I remembered that the last time I had seen the town from that angle it was from the window of a Goose in flight.)

Below: Two photos of a Grumman Widgeon departing from that “postage stamp” loading

ramp in Port Bailey, courtesy of Steve Harvey, renown Kodiak pilot and owner of a

beautiful Widgeon, featured in other articles in this series. I received these photos

a few years after posting this article, and was gratified that my memory was pretty

accurate. Here they make an almost perfect photo-

Our plane coasts off the step in the channel and wallows briefly until our own surf

catches up with us and pushes us forward. In the process, a wave higher than the

bottom of the leaky cabin windows spills a cup or two of water into my lap. Kodiak

Airways’ motto is, “A shower of spray and we’re away.” I decide I’d better write

them a new one about landing. We roar out of the channel and up the ramp at the

Kodiak Airways terminal, and I hang around a little just to see who was the mysterious

figure “along for the ride” in the copilot’s seat. A Dick Tracy look-

As I carried my bag up toward the school I chuckled a little at that story, and yet

a little nagging thought kept intruding. Times were changing, and I didn’t much

like it. Within a few years, Kodiak Airways became Kodiak Western Alaska Airlines

(it had merged with an airline with Bristol Bay and Dutch Harbor routes) and sported

a brand-

Below: Justin Strom’s stunning photo of an early ‘60’s Kodiak Airways Goose at what looks like Parks Cannery in Uyak Bay. Below Right: A Goose pulls up to the ramp in the Kodiak channel, Barometer Mountain in the distance. (Cody Custer, 1975)

This nice graphic of a DeHavilland Beaver appeared in a 1971 edition of Kodiak’s Kadiak Times, as part of an ad for a charter outfit that has long since folded (artist unknown). For more on the Beaver, check out the article, “From Shore to Sky”.

Until the turn of the millennium, longtime pilots such as Fred Ball kept a couple of Gooses flying, under the banner of Peninsula Airways (PenAir). Steve Harvey, son of Kodiak aviation legend Bill Harvey, still flies his lovely Grumman Widgeon for bear hunting and salmon fishing expeditions. (See the article, “Still Flying”) Thankfully, PenAir’s Goose fleet allowed my children to experience one of the authentic joys of living in Kodiak when we took our Goose ride in the summer of 1996. But in 2020, the Grumman amphibians represent an era of Kodiak history that is gone forever, and in some deep, inexpressible way, is sorely missed. Old, clunky, smelly, noisy, drafty, leaky, unforgettable – if you ever got to fly in one, the Grumman amphibians live forever in the most sentimental corners of our memories.

In Memoriam

In closing, a photo of Hal Deirich’s lovely Grumman Goose on Karluk Lake, taken by

Mike Vivion, reminds us of the pilots and planes that have left us. Hal’s Goose went

down near Spruce Island, and he and his passengers did not survive. As I look at

the photo, I can smell the av-

The author poses with a prototype civilian Grumman Goose, replete with couches and curtains,in the Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C. in October, 1997. I eventually noticed that Lindberg’s plane and a replica of the Wright Brothers’ first airplane were hanging overhead. Apparently they had moon rocks there, too. But I was overjoyed to see the Goose get some recognition. And that is why this article is not about moon rocks!

A Peninsula Airways pilot on our flight to Larsen Bay in 1997 uses a GPS to fly through the mountain passes. The bush pilots in the old Grummans had no such advantage!

A Widgeon prototype “up on the step” in this Grumman corporate photo from the late 1930’s.

The famous “Easter Egg” Widgeon on the beach in the 1950’s. The rare top hatch (as opposed to the typical side hatch) hangs open in this shot. Only a few Widgeons with the “coffin door” top hatch were produced, for World War II evacuation of casualties on stretchers. Incidentally, there’s no way to be sure that the photo above accurately color matches the Widgeon’s odd color scheme, but this is based on recollections and written data.

Our 1996 Goose Ride:

The sensations associated with flying in a Goose are seared into my recollections

and mix with the more personal ones as though to remove the memory of a Goose would

be to erase my past. When my wife Debbie and I brought our children to Alaska for

the first time in the summer of 1996, we were able to charter the white PenAir Goose

and land it in Anton Larsen Bay for the sake of the experience. The photos tell

it all; my children sported ear-

Steve Westerfield contributed these photos. On the left is a photo taken from the bow hatch while in flight; I’m surprised the camera didn’t fly away — Definitely not recommended! Below is an unidentified Goose in all its glory, pulled up to a beach, with a family nearby enjoying a fishing expedition.

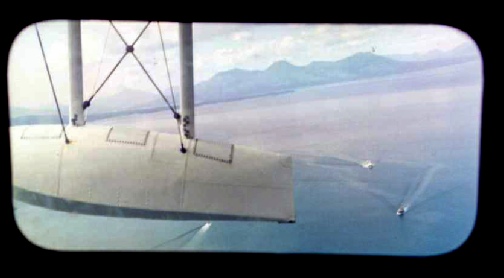

...We took a quick turn around the north end of Spruce Island, looking out across Marmot Bay...

..and then did a water landing in Anton Larsen Bay. Here the pilot looks back while I take a photo of our daughter Kirsti, and you can see the water and shoreline faintly through the window. I snap a photo of a beaming Nate up front.

...and we finish up with a flight through the beautiful pass behind the Coast Guard base (that’s Pyramid mountain to the right) and then land at the ADQ airport.

For more on Kodiak aviation, including much more information on the Goose and Widgeon, and many more historic photos, please follow the links in the photos below.

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-

Then the Goose does a water takeoff, always a spectacular event. “A shower of spray and we’re away,” as Kodiak Airways’ old motto went....

This photo is from around April, and is from a Widgeon. But it is the same gorgeous side view of the Three Sisters mountains as described in the article. The plexiglass windows made a few odd reflections.