Author’s Note:

In my “How to Get to…” series I have recounted the stories of airplanes and steamships traveling to, from and around Kodiak Island. This story is how not to get to your chosen destination, especially at the tail end of an Alaskan winter! It is a cautionary tale about the fickle nature of Kodiak weather, a long journey on foot, and the lesson that you should never take anything in nature for granted. After the adventure, I’ll throw in a few photos of our actual destination, a fine young village named Port Lions, because, of course, that’s where we were trying to get all along. All the photos in this article (mostly toward the end) are from the roll I had in my camera on our grand adventure.

When I graduated from eighth grade in Ouzinkie (see “Ouzinkie School in the 1960’s”)

I was forced to live away from home in order to go to go to high school. I tried

the first year as a freshman to take home correspondence courses, but really hated

it. So off to Kodiak I went in the fall of 1968 to live with Pat and Riley Hunter

and attend the high school there. The next year, I lived with the Finlays, whose

house was at the bottom of Benny Benson Avenue just across the guardrail on Mission

Road. There were a bunch of us boarding students staying there, and it was quite

a little community. My roommate was the late Chad Ogden, the one for whom the “Chad”

Chiniak run is named. In the basement were four kids who came from Port Lions, the

post-

Life in the Dorms

Life in a boarding high school could often be a fascinating experience. The distance

from home and the close quarters with fellow students can foster strong friendships,

as the boarders seek to create some facsimile of a family life away from home. In

the two years I boarded in the short-

How Not to Visit Port Lions

By Timothy Smith

How Not to Visit Port Lions

An Account of an Ill-

Originally posted in the early 2000’s, latest revision in 2020

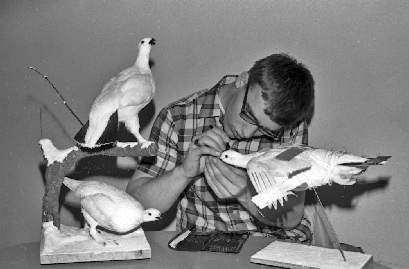

David Robertson in the dorm room in Kodiak with his award-

Not given to frivolity, David was the kind of friend everyone wants beside them in a pinch. A case in point was his quiet way of handling trouble. During the first weeks of the dorm’s occupation in 1970, some of the more exuberant village boys took exception to my role as a student dorm assistant, someone who helped to familiarize the rural students with the dorm’s washing machines and the showers and other accessories of city life. For several nights running, they dragged me down the hall to demonstrate the showers to me (clothes and all).

As annoying as this was, I could not do much to resist, always finding it better

to resort to passivity when vastly outnumbered. After several nights of this, they

made the mistake of coming to get me while I was across the hall visiting Dave. They

traipsed in and announced that it was time for my shower. Aware of their intentions,

David stood up from his studies, looked them in the eye and said calmly, “Tim’s not

dirty.” They scattered like buck-

The youngest of the three Robertsons was freshman Dan. He was the practical jokester

and the most outgoing of the siblings. Inspired by the new classical guitar I bought

from Gerald Wilson, the Russian teacher, he got himself a brand new Harmony and promptly

taught himself how to play. He was soon wailing away with every Merle Haggard song

he could think of, while adding unusual lyrics to old Country classics: “Well, old

grampaw, he’s feelin’ neat, ’cause he stuck his face in his Cream of Wheat, he’s

movin’ on...”, sung sincerely with a high school freshman’s approximation of Hank

Snow. His company was as refreshing as a hearty, spontaneous laugh, which is what

often happened to anyone who spent much time around him. As different as he was

from Dave, he shared the same rock-

The eldest sibling was Becky. Whatever she set out to do got done and was done right.

Her strong Scandinavian genes and early Montana farm-

A Weekend Trip!

On Friday afternoon, April 16 1971, we all got itchy feet to leave the dorm for the

weekend and go to Port Lions. A trip by fishing boat was the long way, around Spruce

Cape and past Ouzinkie, a good four-

The weather that afternoon was glorious: bright sun, patchy clouds, calm winds and

warm temperatures in the low forties. The bright blue sky set off the brown and

patchy white of the thawing hillsides. I packed like I would for a quick weekend

trip: a camera, tennis shoes, a light jacket and a few clothes tucked into my guitar

case (I took my camera and guitar everywhere except to bed back then). The others

were similarly outfitted. Youthful bravado or blind ignorance kept us from remembering

the treacherous heritage of our island climate: early spring is still capable of

sudden relapses of full winter, even in mid-

Our pickup ride to Anton Larsen Bay was uneventful until, about two miles out of sight of the beach, we were stopped dead in our tracks by a broken and abandoned snowplow. An attempt at the first spring road clearing had obviously failed. Not to worry, we told our driver, because it was only a short hike through the snow and around the bend to the beach, where a skiff would be waiting. Thus assured, the teacher drove away, and there began a cycle of assumptions, circumstances and miscalculations which could have proved deadly. For unbeknownst to us, not only was the road closed, but the bay was still frozen over due to a recent cold snap. Our driver assumed we had a ride waiting in the bay below. Our skiff ride turned back at the sight of the frozen bay and assumed that we had also decided to turn back after seeing that the beach was inaccessible. (It was, of course, a full generation before cell phones!) We figured it was a shorter distance to the clear water at the mouth of the bay than to hike along the uninhabited road back to town. Thus we set ourselves up for one of the most memorable nights of our young lives.

Packed Snow and Nasty Surprises

The aforementioned snowplow had broken with good reason. The melting snow had been compacting for months, and still measured close to three feet deep on the roadbed where the plow had been working. On some stretches of the roadbed, where the drifts had gathered, it was still considerably deeper. It was in one of those deep snowbanks that the machine had conked out. We shrugged and set off down the snowy roadbed in the sunshine, still content that this was only a minor inconvenience. The snow which remains on the ground after a hard winter has certain characteristics which do not endear it to the foot traveler. First, a thin, crispy layer of ice forms on the topmost surface. Then, there is a thick blanket of compressed and grainy snow particles, and finally, the ground beneath. However, the drifted snow completely obliterates all hints of the topography beneath, and often hides little streams, mudholes and swampland. To add insult to annoyance, the snow sometimes will support your weight, and sometimes will suddenly give way, plunging one leg or the other a couple of feet lower than the other, necessitating a lot of extra effort to take the next step. Negotiating through this kind of snow was an exhausting task, especially for miles at a time.

We quickly put our outdoors knowledge to work, taking turns “breaking trail” (and warning of surprises) while the others followed literally in the lead person’s footsteps. This meant that the followers were momentarily spared the chore of breaking through the ice layer and discovering what lay beneath the snow. We still had to lift our legs out of each hole and plunge them into the footholes ahead. We soon lost all track of the roadbed, and opted to head directly to the bay down a shallow valley. When my turn came to break trail, I soon discovered that the snow could vary from a few inches to over waist height. I found myself repeatedly using my guitar case to regain my balance and help me out of the large drifts, a process which soon broke one of the hinges. Soon I stumbled upon a patch of thinner snow that headed generally toward the bay, and was dismayed to realize that I had plunged through the snow into an icy stream. My feet, clad in light tennis shoes, soon numbed in the glacial water, but the walking was so much easier because the snow remained thin above the stream. So we stayed with the stream and reached the shore.

By this time even the lengthening spring daylight was on the wane, and as we stood

and took in the significance of the frozen bay before us, I began to hear worried

mutters from my normally stoic companions. A decision was reached to try for one

of the little coves at the entrance to the bay, which were less protected and therefore

likely to be ice-

Becky breaks trail as the sun sets in an increasingly cloudy sky. By this time we

were already well past the end of the road, and after dark our direction became a

lot less clear, as we sought an ice-

We increased our pace as best we could, to take advantage of the remaining twilight.

Becky sloshed off in the lead, and in some manner we trekked on behind. Soon all

light had faded, and with the thickening cloud cover we could not see any stars.

There must have been enough moonlight to break through the clouds, for we were eventually

able to dimly distinguish the trees from the snow. The appointed hour of our rendezvous

with the skiff had long passed, as had suppertime (we had, of course, brought no

food)! Dan and David began talking softly to each other in uneasy tones again. It

had never occurred to me to worry, and my friends were considerably more accustomed

to cross-

Sometime around midnight I had fallen to the rear. As I passed a solitary tree in

near total darkness, I slipped down the incline of crusted snow beneath its branches

and lay where I fell. I felt as though I could not move. Suddenly my only thought

was to sleep. Dave, suddenly aware of my disappearance, called, turned and grabbed

me. Roughly and firmly, as only a poker-

A Temporary Shelter

At last, sometime long before dawn, our feet felt the snowless rocks of shoreline

(an ice-

We had been walking for many hours, with very slow progress in the deep drifts, and

now that we reached the beach, it was anybody’s guess which direction we should go.

We gradually ascertained that the beach to our left seemed to curve away from the

iced-

Just a bit tired! Becky stands by the bunk beds in the cabin we stumbled upon in the middle of the night. Dan is still huddled under the damp sleeping bag he found on the top bunk. We stayed here until daylight. Many thanks to the unidentified owners of this cabin, who left it unlocked, God bless them. I never wondered what was in the sacks (or even noticed them) until I recently scanned this picture for this article.

Becky took charge again, and ever-

A Mysterious Benefactor

The next thing I remember it was mid-

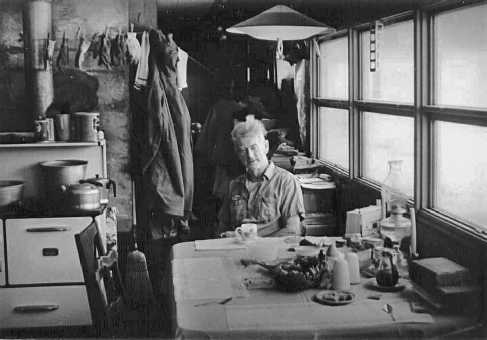

Our “Good Samaritan,” at the table he spread for us after we had all awakened. If anyone knows the identity of this wonderful man, please email me. We most certainly thank him for hospitality and generosity!

A gallery of rescued kids! Left: Tim (the author) groggily awake. Right: Dan, looking equally zonked out after our journey. The calendar is from O. Kraft and Son, Kodiak, and the date is Saturday, April 17, 1971. Above: Dave relaxing on the couch, with his best “What did we just do?” expression on his face.

The rest of the weekend was anticlimactic. A quick call or two using the homesteader’s

CB radio assured two sets of parents that they still had us as dependents. As soon

as the wind died down, the skiff from Port Lions arrived and took us there without

incident. We were sitting around the Robertsons’ table for supper that evening,

energetically spinning tales of our grand adventure. On Sunday morning I accompanied

Dan and Becky to the little missionary chapel there in Port Lions (Dave never shared

our enthusiasm for such things) and discovered to my dismay that my well-

This was not too surprising, since I broke a hinge on my guitar case while using it as a snowshoe earlier! Dan remarked that there would soon be a thoroughly converted Kodiak bear out there somewhere, come thaw. I laughed and soon forgot about it. That summer at Camp Woody, Susan Horn presented me with a shapeless mass in a clear plastic bag. It was what was left of my Bible. She had found it under a tree while hiking a couple of miles past the road at the end of Anton Larsen Bay!

Postscript

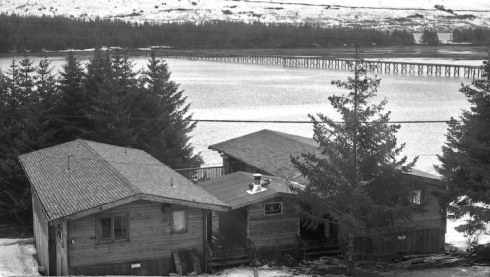

Our destination was Port Lions, and by golly, we got there. Port Lions was only

about six years old when I got there, having been built new from the remnants of

Afognak and Port Wakefield. Below are some shots of the Robertsons and the village,

from the same roll as the previous photos. It was a wonderful visit, and I would

have enjoyed it a lot more if we hadn’t taken so darn long to get there! I was impressed

with the modern homes, the roads and vehicles (still rare for villages back then)

and the swanky-

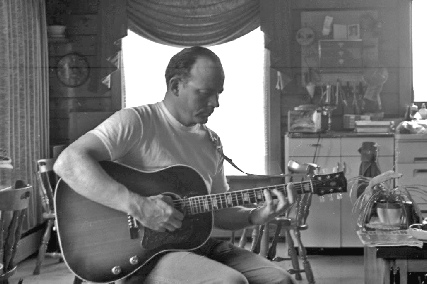

Top Left: Mr. Robertson (the elder Dave) was quite the guitarist, and had done some Country and Western performing in his younger days. He also was the radio dispatcher for the Wakefield Cannery. One of the stories he told was how a very drunk fisherman had waddled into his radio shack demanding that he call Kodiak Airways. “Call me a Goose!” (as in a Grumman Goose), he demanded. “Ok,” replied Mr. Robertson, dryly, “you’re a goose!” Daniel must have picked up his sense of humor from his dad!

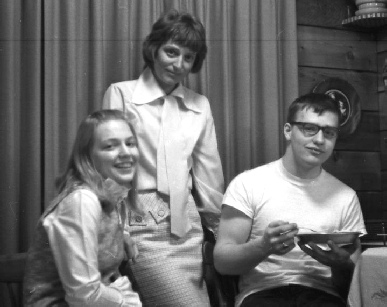

Bottom Right: Mrs. Norma Robertson and Becky and David, who once again found his appetite!

Top Right: I was amazed at “The Chateau” (or a grand resort at the very least): the beautiful Wakefield Fisheries cannery at Port Lions. Unfortunately, like the OSI cannery in Ouzinkie, it later burned down, and was not rebuilt.

Bottom Left: Many of the homes in Port Lions were newly-

For more on Kodiak aviation and boat travel, including much more information on the Goose and Widgeon, and many more historic photos, please follow the links in the photos below.

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-