Introduction to the 2020 Revision of the Original 2005 Article

As an English Language Development teacher in the Pomona Valley of Southern California

in the late 1980’s, I had the distinct honor of helping many newly-

The Old Fishing Boat

Hidden in a junkyard off a nondescript street in the Pomona Valley is a large packing

crate, about the size of a semi-

The cluster of people are refugees, and all of them left Viet Nam in boats similar

to the one they are touching now. A closer look at the boat reveals a shallow draft

and low transom, with pointed prow and stern. In the rear of the boat, mounted on

rotting beams, is a rusty and corroded one-

A photo of Lora Pham’s escape boat in 1980. She provided the Vietnamese caption.

One of the bystanders is Madalenna, a former refugee who arranged for transportation for the boat. She is proud of the new arrival, and speaks of plans to place it in a museum that will showcase the stories and successes of the “Boat People.” But she is also suspicious, for having escaped a regime of great brutality and repression, she is not at all convinced that the boat is safe here. There are those who would destroy it, she feels. Even the ideological and geographical gulf that separates her from her homeland is not quite far enough to avoid the tentacles of a fear that is never far from the minds of these refugees. Madalenna is not her real name, but one that she adopted when coming to her new country. These refugees have changed their names, often several times, to make it harder to be recognized or tracked. It is a life perspective that those raised on these shores in freedom might find excessive, even paranoid. Nevertheless, these who have suffered feel justified in keeping it.

The tall English-

After the war, the Vietnamese Communists confiscated all maps, in hopes of deterring escapees. Mr. Beery pulls a tiny world map out of his pocket and explains that this map was included in a small notepad that was for sale in Viet Nam, and was overlooked by the authorities. The South China Sea looked like just a thimble full of water on the tiny map, yet the map was used to navigate the hundreds of miles of open ocean between Viet Nam and Malaysia, where Beery got it from its former owner. One piece of the navigational puzzle remained—a compass. Beery retrieves from his pocket a battered, G. I. issue field compass, which a Vietnamese man bought on the black market to use in his escape.

Using the tiny map and battered compass, the refugees had negotiated the long and treacherous journey to freedom from Viet Nam to Malaysia. Then Beery pulls out a laminated ID card bearing the name and photo of a teenage Vietnamese girl. He shows it carefully to each of the group of former refugees gathered by the boat. No one recognizes her. He explains that he found it on a beach in Malaysia along with rubber sandals and other debris shortly after one of the refugee boats was reported sunk. There is always hope that, what with the changed identities and confusion in the aftermath of war, she may one day be identified, living peacefully in freedom. But Beery fears that she is one of the hundreds, perhaps thousands, for whom their perilous boat trip was their last.

Another person standing near the boat and touching the aged boards is named Lora.

That is what we call her now, but in her other life she had a different name. Standing

beside the crated artifact she begins telling details of her own journey. “I feel

very proud of my escaping from Viet Nam,” she says. “This boat is evidence of my

story and other people’s. I still wonder about my decision to leave, and how we made

it because God helped us. My husband spent two years in a Communist reeducation camp

because he had been an engineer at the civilian airport in Saigon. Just working with

the South Vietnamese in that way was enough to put him in prison. I remember when

I first discussed leaving Viet Nam with my husband. He said ‘Only the deaf do not

care about the gunfire.’ We knew that if we stayed, our sons would have to become

Communist soldiers and fight in Cambodia. They would have no chance for a higher

education. We decided to leave, even though there was a 99% chance we would die at

sea. We left in a thirty-

The forty-

The sign at the entrance of the refugee camp in Indonesia. People all around the world opened their hearts to these refugees, and their success in their adopted countries has been nothing short of miraculous.

Conclusion

There are certain objects that define us, catch our imaginations, connect us with our heritage. Old Ironsides, the U. S. S. Arizona, the Titanic, even Noah’s Ark are aquatic symbols that represent independence, treacherous attack, human frailty, or judgment and renewal. The old river fishing boat in the crate in a Pomona junkyard also symbolizes certain ideas: the desire to have liberty, the sacrifices that are necessary to live free, the miracle of Divine intervention and the power and magnitude of the human spirit.

For the other articles on the Vietnamese-

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-

The Old Fishing Boat – A Vietnamese Escape Adventure

By Timothy Smith, Originally posted in 2001, latest revision in 2020

The Old Fishing Boat – A Vietnamese Escape Adventure

One of Three Articles About the Vietnamese-

One of the original refugee boats taken by many South Vietnamese folks escaping the Communist regime of Vietnam, in the years after the fall of Saigon in April of 1975. Some boats made it to Indonesia; this boat landed in the Philippines, and was donated by the that government to be part of a traveling museum in the United States. Its first stop was in Pomona, California.

Addendum: Some of Lora Pham’s Story in Photos

From Lora’s story we can read between the lines: no one brought their favorite china

cabinet and Grandma’s easy chair along on that little fishing boat. Lora managed

to bring just a handful of photos, which I have scanned below. The actual conditions

of travel for forty-

The original flag of The Republic of (South) Viet Nam, a country which no longer exists. The author at “The Wall” in 1997. A small flag near the name of someone’s relative.

Left: A young Lora Pham in her garden. Right: Lora Pham weds Henry Pham, becoming Ba Hien Pham (Mrs. Henry). Dates unknown.

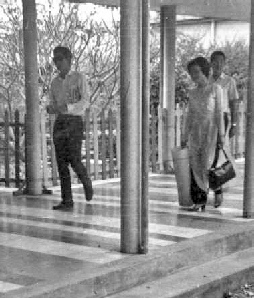

Left: The only extant photo of Lora Pham as a college professor, shown here walking between classrooms with two of her students. (Date uncertain).

A South Vietnamese educated person, especially a professor under the old regime, would face severe employment restrictions or even be sent to the reeducation camps.

Lora’s husband, Henry Pham, worked at Tan Son Nhut airport on the commercial side, for Pan Am, with no military connections whatsoever. He still was forced into a reeducation camp for two years. When he was released, he found employment to be very difficult due to the extreme measures he was subjected to.

Left: Lora Pham the Instructional Aide (2000 photo). Right: Lora and Henry’s anniversary, around 2004, taken in the back yard of their home in Montclair, California.

These are not bitter people! Lora has since retired from Chaffey Joint Union High School District, as one of the most respected and honored Categorical employees in their history. Henry has faced the limitations of language, culture, and especially the ravages of the reeducation camp he endured under Communist government. But Henry has become active as a Buddhist lay leader in the Southern California Vietnamese American community, and is one of the most upbeat and positive people I have known.

Lora knows hundreds of people, keeps track of former students and fellow (former)

refugees, and is one of the most pro-