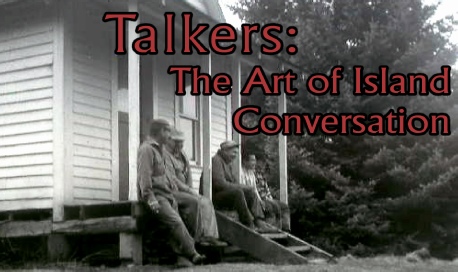

Talkers — The Art of Island Conversation

By Timothy Smith, Originally posted in 1999, first revision in 2020

Talkers (the Art of Island Conversation)

Kodiak Island Storytellers Through the Years

The logo above shows a group of men in Ouzinkie, Alaska relaxing and chatting on Fred Muller’s front porch after completing spreading gravel on one of the main trails through town in the fall of 1965.

Introduction to the 2020 Edition

This little article was one of the first five I posted to this site back in 1999. This is its first revision. I’ve made almost no changes to the original text, but added photos to help tell the story. As someone who no longer lives in a small Alaskan village surrounded by wise elders and colorful rural eccentrics, I find that I miss the flow and cadence of the conversations I overheard as a child. When I wrote my novel, Morning for Sokroshera, I borrowed heavily from some of the older generation who befriended me when I wrote my entirely fictional tale. Trying to get the rhythm, flow, and music of their talk was a major challenge for me. This 1999 article was my first attempt at appreciating those wonderful people. Here it is, unedited, but with new photos. — Timothy Smith, February 2020

“Talkers” — The Original Article

Colorful Rhetorical Styles

Long time Kodiak island residents are champion talkers. A visitor who spends any time around local Kodiak residents or stays for awhile in one of the island villages will soon become aware of this inescapable trait. In fact, many rural residents of the Kodiak archipelago possess a spontaneous rhetorical style and a command of colorful local expressions reminiscent of something penned by Mark Twain or Joel Chandler Harris. There are several reasons for this, not the least of which is the fact that old timers were deprived of the canned entertainment of satellite TVs and rented videos, and had to entertain each other with local legends, gossip about relatives or humorous asides about recent local events.

As a young boy in Ouzinkie, one of my favorite things was to visit the Opheims down the island in Pleasant Harbor and have a talk. In the days before the Tidal Wave we would be frequent visitors to the Opheim’s place, and I would sit spellbound while the adults would swap stories. Several colorful books of tales by Ed, written when he was already older and retired, provide a rare opportunity to enjoy some of his tales in print. But I can vouch that his late wife Anna was his equal at storytelling. The many happy visits around her kitchen table helped me learn to cherish the wonderful stories and colorful oratory of the islands. (Continued below…)

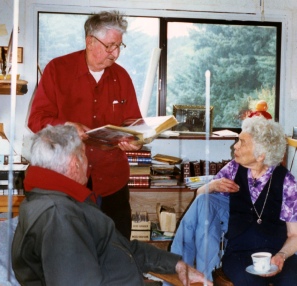

Ed Opheim examines an old photograph in 1967 (Below Left) and chats with my parents, Norman and Joyce Smith in 1992, in his home high on a ridge overlooking Pleasant Harbor, Spruce Island, Alaska

The When, Where, and How of Local Talk

In the days before prefab government housing invaded the villages, the typical native

wood frame house did not even contain a living room. In its place, homes had large

kitchens, and family life centered around the cookstove and a large, oilcloth-

The stories would fly and voices would rise and fall in a cadence impossible to duplicate

in print, as the eager participants alternately shared hearty laughter or solemn

head shaking and tongue clicking, as the subject required. And of course, the object

of the game, aside from the obvious enjoyment of neighborly company, was a subtle

but definite contest of one-

The rural style of conversation was not limited to the warm and cozy environment of the kitchen table. In every chance meeting on the dock or along the beach the same rules of rhetoric would apply. Even today, many a rural Kodiak Islander will bend your ear with unbelievable skill if given half a chance. Under no circumstance will an experienced village storyteller content himself with going logically from point one to point two. With great flourish, the storyteller will spend time with you in a way that few adults steeped in modern culture have the skill, patience, or inclination to do. It can be taken for granted that you will be treated to a tale filled with so much hyperbole and colorful metaphor as to make your head spin. But in your rural friend you will find a listener of such sincere focus that even a paid psychologist could not hope to duplicate it. And months later, your friend will repeat back something you told them and ask how that situation is going now.

Not that the local loregivers look like they are talking or listening to you; instead,

experienced communicators look past each other, out the window, down the channel

or anywhere other than straight into each other’s eyes. One of my clearest memories

of village life is the way a small group of conversants, sitting on the dock or a

porch or the side of a beached skiff will stare off in roughly the same direction,

while paying complete and enthusiastic attention to each other. I have seen this

verified in old photos. At appropriate points in the discussion, when a question

needs an answer, or when the speaker needs a good-

Left: Peter and Mary Squartzoff celebrate their anniversary, 1968.

Peter would tell me stories and jokes when I was a kid, if I ran into him on the trail from the store, or while walking on the dock. He would rarely look straight at you after saying hello, and that was normal talking procedure.

Right: I ask Herman Squartzoff, their son, a question at the memorial service for my Mom, 2006.

Most of the time we both felt comfortable looking elsewhere while chatting. Mary, Peter, and Herman have passed on now; “Memory Eternal.”

Above: Tim Panamarioff, Sr. chats with Dan Soderberg in Ouzinkie in 2005.

I love this photo, and I took it very surreptitiously, because I didn’t want a pose, or to impose! These elder statesmen are not talking about the bung on the 55 gallon drum! They were chatting seriously, and defusing the intensity with looking at some other thing at the time. The barrels, pump (behind the plastic bucket), the overturned skiff, and the forest beyond is pure Ouzinkie village back yard!

An Absorbed Style With a Practical Purpose

I suppose such a culturally natural manner of conversing is hard for a newcomer to

adopt. It is certainly hard to shake once it has been absorbed. Imagine my chagrin

when, as a village-

Although missing something in print, it may be possible for me to replicate the vocabulary

and stylistic elements of local storytelling. There are some creative components

that are common in all the stories. The first characteristic is a delicate self-

What this little story did not include was the chilling reality, lost on none of us at the time, that if her seams had opened up while he was far from shore, Eddie might have quickly been one of the many new residents of Davy Jones’ Locker. The speaker had a practical purpose for his tone. The implicit blame that Eddie bore in seafaring culture for not taking better care of his boat was more than blunted by the humorous spin of his tale. Also absent from the story, but in the local shorthand easy to assume, was that Eddie had spent an extra long time with boat nails, cotton, tar, and a caulking gun before he ever dared float his little seiner again. It would be no exaggeration to assume that Eddie’s boat spent that season with the tightest, most seaworthy hull of the fleet! Dad, not having any good beaching stories handy, and not being inclined to cast aspersions on another seafarer’s plight, laughed heartily and moved on to the next subject of conversation, thus completing the cycle of confession and absolution. (Continued below…)

Above: A local fisherman has painted his seiner, and is about to apply copper bottom

paint, mid-

Notice the black lines toward the stern: loose seams have been caulked with tar.

Boats, weather, skippering ability… all of these are good subjects for a fine story

to be told, with humor, understatement, hyperbole, and self-

Rhetorical Sharpness, But Hidden Warmth

Another important element in village storytelling is to pretend that you don’t know

as much as you really do, to keep your audience guessing or allow the listeners to

read between the lines, and of course to achieve maximum humorous effect. A master

of this style of tale spinning was Jenny, a dear friend of mine who was like another

grandma to me in my early years in Ouzinkie. I had the great honor of visiting her

on several occasions in the 1990’s, when she was well over ninety years old. She

welcomed our family into her astonishing little cottage, a rare remnant of cozy old

village homes with its low ceilings, small rooms and cheery "kellydoor" sun porch

filled with brilliant potted flowers. As we gazed appreciatively at the reverent

corner of beautiful icons, and the sideboards laden with a collection of great-

Jenny caught the drift of my ensuing questions immediately. “Oh, I don’t like the TV,” she averred. “There’s too many no good things on it. I saw two grown men just jumping on each other. They were throwing each other around and stepping on each other. I couldn’t understand why the crowd was cheering when people were beating up each other. It was horrible. I got up and shut it off. No good stuff on that TV.” Jenny shuddered dramatically and paused for maximum impact, witnessing our faces as we visualized the image of a nonagenarian village matriarch watching World Federation Wrestling for the first time. Presently she added, “But I do like Barney the purple dinosaur!” Then she admitted that she was a regular watcher of “The Golden Girls,” thus letting us know that our legs had just been thoroughly pulled. Knowing Jenny as I did, I should not have been surprised that she would not only be able to figure out the TV culture, but also keep herself distant from it.

Jenny possessed a warm-

On the occasion of our family’s visit with my parents in 1996, it was the first time

I had seen her in over twenty years. She greeted my Mom, who was nearing her eightieth

birthday at the time, as “My Girl,” then promptly began complaining loudly to me

about a photo I had surreptitiously taken of her back in 1976. In this way I was

led to understand that if I took a few more pictures it would be ok. Understatement

and implication were always her forté, as when one day in the mid-

Above: Jenny and me having a good talk in her house in 1996. Below Left: my Mom,

Joyce Smith, visits Jenny on her rounds as Village Health Aide. Below Right: Jenny

in mid-

Some With a Less-

The champion talker will of course incorporate all the rhetorical elements I mentioned

and invent a few more. Some of the most memorable talkers also exhibit a less-

When I awoke, I noticed that I was not alone, for there was a figure of a man walking

in my direction. I got up slowly from behind the log which partially obscured me,

careful to gradually announce my presence so as not to invade his privacy. The rules

of encounter in such cases are that if you wish to remain incognito (the privacy

of your walk being already shattered by the presence of another) you may wave and

continue on your way without troubling each other. Ted was of the mind to make contact,

and so ambled up to me. He was of about my height, with a long shock of whitish hair,

a scraggly gray beard and a tight pair of old blue jeans which were held up with

a belt and an enormous buckle. I mention this because somewhere in his travels, Ted

had abandoned his shirt, revealing a large barrel chest. He looked at me intently,

revealing that he had once lost an eye in a misadventure that I am not party to.

We approached each other until we reached the arm’s-

“You’re not one of them religious guys that doesn’t smoke are you? I need a smoke.” Such pleasantries aside, Ted launched into an explanation of his activities on the beach. “I walk on the beach to stay in shape,” he declared, pulling in his chest with all his might. Presently he exhaled mightily, and the chest exploded back into its previous dimensions, an exercise he thankfully did not bother to repeat. I politely occupied my attention with a boat in the distance. “I like looking up and down the beach for useful stuff. I find a nice piece of driftwood I could use, and I carry it for awhile, then I find a better one, so I throw the first one away. You know, by the time I get back home I got nothin’ in my hands!”

As I was processing this, I noted his hands, one of which was partially wrapped with

a crude bandage. As if in anticipation of my next question, Ted continued: “Oh, I

chopped the end off my thumb with an ax.” He gesticulated in the general manner of

one who has just accidentally guillotined an appendage, as if his words would not

suffice. “Didn’t have any ice to put it in, so I just threw it away.” Again he acted

out his words, tossing an imaginary thumb into the underbrush. I mumbled something

about doing something, and he waved me off. “Oh, don’t worry about it! It’s gone

now, anyway. I started to get worried about my thumb, what with that bone hanging

out and all, so I rode into town. I got tired of looking down at that bone. They

were real happy to see me in the emergency room. The nurse said she wanted to carve

off a piece of my butt and stick it on my thumb. I looked at her and said, ‘Look,

I’m sixty-

The Skill of a Master Storyteller

Before I could finish visualizing his word picture about the reconstructive surgery, he was off again with his narrative: “That nurse said thank you for coming and gave me all kinds of peroxide, mercurochrome, iodine, Clorox and such to put on it, and sent me home.” At this he raised his hand and tentatively wiggled his bandage. “Should heal up pretty good. You sure you don’t have any smokes?” With that he turned on his heel, picked up a nearby piece of driftwood, and walked down the beach. As I walked back through the woods, my thoughts remained captive to his tale, and to this day, the longer I think about it, the worse it gets. Such is the skill of a master storyteller. End of original article

Conclusion: Three types of talk, featuring my Dad, Rev. Norman Smith

After reviewing this original 1999 article, I thought of photos to add to illustrate the text. As a way of concluding this revised edition, I’ve included these three old photographs of my Dad in action, because they help to explain his way of communicating with people.

Above: the serious conversation in a casual location — Dad turns to the fisherman to ask a question or express his sympathy, all while holding a coffee mug. Bottom Left: Dad speaks with a visiting dignitary, while the driver of the car, Bill Stone of the Kodiak Baptist Mission, who is undoubtedly grateful not to be the focus of the man’s scrutiny, just stares at the camera. Dad’s uniform is all “captain of the Evangel,” and no “Baptist Missionary.” Bottom Right: Dad addresses a formal gathering of local luminaries at the Rotary Club in Kodiak, doubtless with his version of the “formal remarks” that are called for on such an occasion, and doubtless more of a fish out of water than even with the dignitary. From left: Rev. Bob Childs, Dr. Bob Johnson, and Father Bullock.

I can tell you on good authority that Dad’s style of speech in all three situations would not have varied very much. He spoke plainly, with unadorned, clear vocabulary, and a direct way that was very effective because of his obvious sincerity. The part of his job that he loved the most was in the top picture, talking informally with the folks on the dock or at “mug up” in a cannery, or even in a local bar (after ordering a soda!)

He could stare off into space during a conversation along with the best of them,

and hold his own in recounting a good story. But his penetrating yet non-

For more on Kodiak history, including much more information on the Evangel, Camp Woody, the village of Ouzinkie, and island transportation, plus many more historic photos, please follow the links in the photos below.

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-