A colorful procession of South Vietnamese flags (now a symbol of the Vietnamese-

Introduction to the 2020 Re-

This article was written ten years before I retired from teaching. I have changed

very little. I went to the 2010 celebration in Westminster, and took lots of photos

there, also; all photos not labeled from 2010 are from the original photo session

of the party in the street. It’s hard to explain how fun these celebrations are;

although the flags of their old country are everywhere, it’s the flag of a country

that no longer exists, and these folks are enthusiastically American now. They don’t

make excuses, they don’t demand help from government, they don’t wallow in self-

Introduction to the 2008 Posting: “A Nation of Immigrants”

America is a nation of immigrants. The topic of immigration has so dominated the

news that we may have lost sight of that fact. An immigrant community is a population

that has been transplanted (and in some cases uprooted) from the home country and

has found a home in ours. And there is nowhere in the United States where the blossoming

of an immigrant community is more on display than in Westminster, California, on

Tet, the Vietnamese New Year. I have had close contact with the Vietnamese-

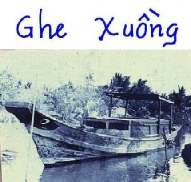

But the Vietnamese community has a start date: They began to reach our shores in 1975 after the fall of Saigon, and then by waves, in the early 1980’s when thousands took to the seas in small boats, escaping to Indonesia, the Philippines, and eventually to the United States. The experience of Mrs. Lora Pham in one of those small boats is chronicled in the article I wrote in 2000 called “The Old Fishing Boat (A Vietnamese Escape Adventure).” In that article, I described an old refugee boat that the Vietnamese community had received from the government of the Philippines. This article contains a major update involving the current career of that boat. It is also a celebration of a vibrant group of Americans who have bloomed where they were planted, who have risen from the ashes of their country to become enthusiastic, successful Americans.

Right: The boat Mrs. Pham escaped in, as it looked in 1980. Follow the link in the text above for that amazing story. (Photo and inscription courtesy of Mrs. Lora Pham)

Left: A group of high school students pass down Bolsa Avenue, where the signs of the local businesses are almost all in Vietnamese, in the heart of Westminster’s “Little Saigon.” The emblem of a country that is no more, the South Vietnamese flag now represents cultural solidarity rather than political power.

Tet in Westminster, California

It is a Saturday in early February in 2008, and thousands of people line the streets

in Westminster, in the heart of Orange County California. On this weekend, the Vietnamese-

This group’s banner helps to explain the flag. The three red bands on the flag of South Vietnam stand for the regions around Hanoi, Hue and Saigon, the three main regions of the country.

When South Viet Nam fell in 1975, the entire country came under extreme Communist rule. The majority of these immigrants wish for a unified, democratic country. Many families are still trying to get loved ones out of the country and out of the oppression that is still prevalent in Communist Viet Nam.

The parade begins noisily with a Westminster fire truck festooned with American flags, the firefighters in yellow suits waving enthusiastically and setting off the sirens and horns. Then there is a large group of young people waving bright yellow flags with three red bands across the center: the symbol of South Viet Nam, a country which no longer exists. The flag is now a cultural symbol, waved in celebration of survival and freedom in a new land. There must be hundreds of those yellow and red flags, but there are nearly as many US flags as well. This is a group of immigrants who are extremely grateful to be Americans!

The lady on the left sports a traditional dress made from the colors of the US and South Vietnamese flags, while the lady ahead of her carries Old Glory.

This says it all: the ARVN (South Vietnamese Army) veteran in the red beret proudly waves at my camera.

His message says: “America believes in fighting for world peace, saving lives for all people, and maintaining freedom. Thank you Army, Airforce, Navy, Marines, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine and Reserve for making my family and I proud to be American.”

Left: A group of dragon dancers and a beauty in traditional dress work the crowd as they wait for the next float to pass by. The two men on the right will spot the dancers when they get tired.

Another dragon team comes over to our side of the street as a third team passes by. In person, the colors of these costumes almost defy description.

The parade continues with Buddhist and Catholic youth groups, colorful dancing troupes,

and many units of veterans of ARVN, the South Vietnamese Army. There are frequent,

poignant reminders of the long and difficult struggle these people have experienced. And

one of the most tangible reminders is still to come. But this is Orange County,

Southern California, just weeks before a Primary Election, and most of the adults

in the crowd are American Citizens and registered to vote. In a quintessentially

American scene, seemingly every elected official and candidate is in the parade,

mostly in the back seat of classic convertibles, waving and calling out to the crowd. A

Latino US Congresswoman, dressed in a flowing traditional Vietnamese pantsuit, jumps

out of her vehicle to pump the hands of the onlookers, shouting “Chuc Mung Nam Moi

(Happy New Year)!” Not a few of the elected officials are Vietnamese-

A marching band from the local high school shows the diversity of Westminster: about

half seem to be Vietnamese-

A New Friend

An elderly gentleman beside me named Trinh strikes up a conversation, asking if I

am a Viet Nam veteran. I am not, but we have an animated conversation about the

war, the aftermath, and his own journey to this country. I share with him my experiences

with the Vietnamese-

The only hint of regret in his voice comes when he reminds me of what so many in

his community feel, that “If only the Americans had kept up the bombing of the North

for a few more days, the Communists would have been defeated.” It is an opinion

shared by a wide swath of Vietnamese-

The 2008 Tet Celebration in “Little Saigon,” Westminster, California

– Featuring the “Old Fishing Boat” of a previous article

By Timothy Smith, Originally posted in 2008, latest revision in 2020

The 2008 Tet Celebration in “Little Saigon”

A Vietnamese-

One of Three Articles About the Vietnamese-

A local high school orchestra specializing in traditional Vietnamese music has a

blend of European-

The Westminster Police keep the crowd back as one of the more elaborate floats passes

by. Well-

The “Freedom Boat” Begins its Tour

Finally, near the end of the parade, an old cab-

And so the old boat is a reminder for all of us, that we are indeed a nation of immigrants,

that freedom comes at a price, and that America is still a place of refuge and opportunity

for those “huddled masses yearning to breathe free” as the old poem states. My friend

Lora Pham waves excitedly to me as she passes in the boat, happy to see that I made

it to the parade. Madalenna Lai, the boat’s curator and the organizer of its tour,

also recognizes me and waves. What a privilege it is to be a friend of the Vietnamese-

The refugee boat, a gift of the Philippine government, approaches on its flatbed,

with flags of all the countries that assisted the refugee “Boat People” displayed

at its stern. The boat was embarking on a 50-

(Left to Right) Ms. Diep Fintland, my good friend Mrs. Lora Pham, and Mrs. Madalenna Lai (the curator of the boat museum) greet me enthusiastically as the boat passes by, while Mr. Ky Linh Nguyen, out of camera view, greets the parade watchers on the other side of the street.

The banner proudly announces the 50-

The voyages of boats such as this mark one of the most daring escapes in history! Imagine this boat (designed originally for river fishing) filled with thirty or forty people, trying to make it to the Philippines or Indonesia from coastal Viet Nam! (Check a map!)

Shopping in “Little Saigon”

The parade concludes with a float featuring a Rose Parade Princess who is Vietnamese-

A child dances in the confetti, which is released with a loud bang from tubes such as the ones carried by the lady in pink. The red, white and blue banner in the center of the photo is a candidate’s poster; all the local politicians were out in force!

Left: A child and her grandfather stand outside the indoor shopping mall in “Little

Saigon.” The statues speak to a long and rich cultural heritage, now preserved in

the middle of Orange County, California. Right: A grinning statue representing Buddha

greets shoppers in the indoor mall, a reminder that the majority of Vietnamese-

A colorful statuary shop caters to the Vietnamese Catholics. The freedom of religion

the immigrants experience in the United States is a far cry from the Communist-

Left: Near one of the entrances, a row of lifelike store mannequins causes a double-

In the tiled hallways of the mall, both upstairs and down, troupes of dancers with the traditional colorful dragon and old man (representing the chasing out of the old year) happily accept red envelopes containing money from shoppers and shopkeepers alike, preserving the tradition of good luck that is centuries old, all to the loud rhythm of large drums. The dancers take turns beating the drums with large sticks as the dragons bob and weave, occasionally opening their colorful mouths to accept red envelopes from cautious children. The colors of the costumes verge on the psychedelic, an impression that’s reinforced as the dances become more animated. A sense of excitement is everywhere, and in the crowded hallways everyone seems to appreciate my presence and politely give way for my camera. Several people stop to explain to me what the dancers are doing, with smiles and gestures and an impressive command of their new language. This community is happy to share its joy in their new year and in their new life!

Left: Two dragons dance to the beat of the drums in the upstairs hallway of the mall.

Below: The old man, representing the old year, watches as a child prepares to give

a gift to one of the dragons, as shopkeepers watch through the window. The act of

placing an envelope into the mouth of a fearsome-

Left: A riot of color spills over the curb and into the street in the happy aftermath of Tet 2008.

Scenes from the 2010 Tet Festival in Westminster

Above: Tri Ta, on the Westminster City Council, is a sign of things to come. Vietnamese-

Right: Two members of the Westminster Youth Committee show off some cool face paint.

Below: two pageant queens, crowned (apparently) by a classic car rental company.

Left: The simplest parade entry ever! The signs say “Happy New Year” in Vietnamese.

Below: A much more elaborate float put together by a Vietnamese-

Above: After the parade, we got some great food, even though the guy on the left seemed to be upset about it!

I personally like being around people who like to read!

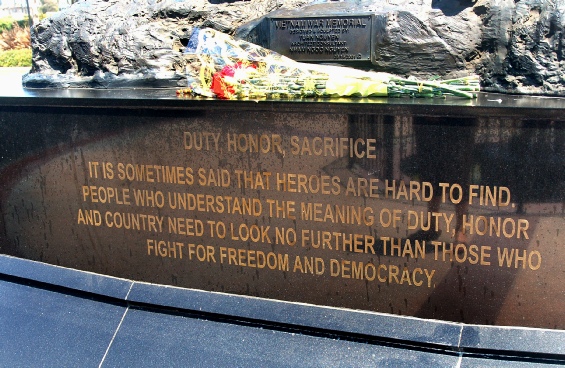

Scenes from the War Memorial

The U. S. and South Vietnamese flags, along with the POW/MIA flag, fly over an eternal flame and the above inscription at the Vietnam War Memorial in Westminster, California.

The original flag of The Republic of (South) Viet Nam, a country which no longer exists. The author at “The Wall” in 1997. A small flag near the name of someone’s relative.

For the other articles on the Vietnamese-

To Find Out More About Tanignak.com, Click HERE

To Visit My “About Me” Page, Click HERE

To Return to Tanignak “Home,” Click the Logo Below:

Information from this site can be used for non-